The full name of the exhibition is Istanbul As Far As The Eye Can See: Views Across Five Centuries. The venue of this most interesting exhibition is Meşher, at 211 İstiklal Avenue. Entry to the building is from the side street (Postacılar Sok.) around the corner. Readers may recall Meşher from another exhibition that was the subject of a previous post on this site; namely, “At the Art and Culture Hub of the City: The İstiklal Avenue”. The more than one hundred years old historical building belongs to Ömer Koç, the current Chair of the Board of Directors of the Koç Group of Companies. For information about the Koç family and the Koç Group, you can refer to the post, “Mirror of Industrial Heritage: The Rahmi Koç Museum”. Both posts can be easily accessed by means of the respective links.

The current exhibition at Meşher opened its doors on September 20th, 2023 and will end on May 26th, 2024. This is a unique occasion where more than a hundred rare pieces of the rich private collection of Ömer Koç is revealed to the public eye. The exhibition consists of a variety of depictions, books, rare photographs, albums, artefacts, souvenirs, diaries and letters through which a both visual and verbal panorama of Istanbul across centuries is provided.

Frans Vervloet (1795-1872)

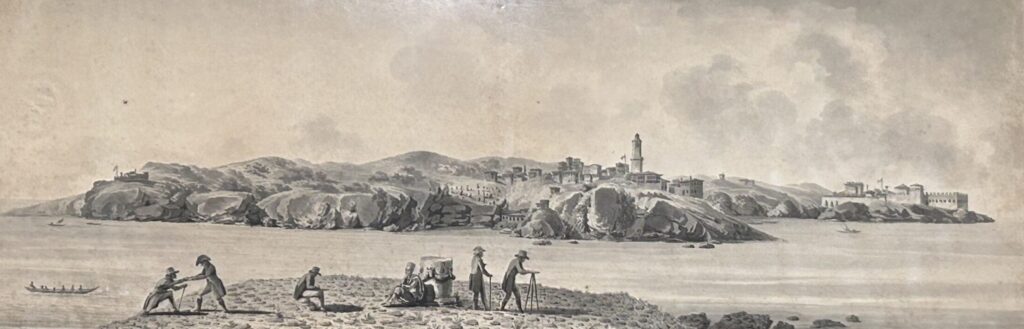

With Remarks on the City of Constantinople

Book written by Frederick Calvert, 6th Baron of Baltimore Illustrated by Francis Smith

Istanbul has been a point of attraction for outsiders ever since its foundation as a city (Byzantium) in the 7th century B.C. by the Greek warrior Byzas from Megara, Greece. However, it is known that human habitation within the boundaries of today’s city of Istanbul goes way back to the Paleolithic period. Excavations at the Yarımburgaz Cave in Başakşehir (Istanbul) have revealed human life dated to between 600,000 to 400,000 years ago. The findings are considered to be testimonies to the great migration of Homo Erectus from Africa in the direction of Europe.

Published by F. Löffler (End of 1890s)

Michel-Francois Preaulx (c. 1748-1832)

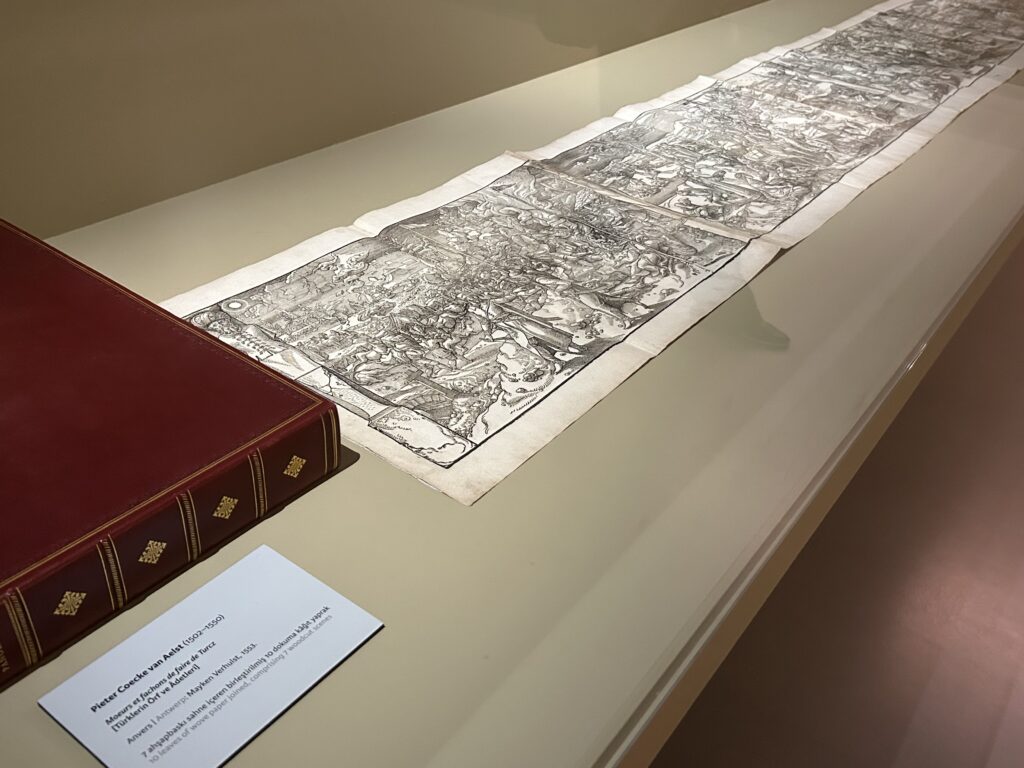

Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550)

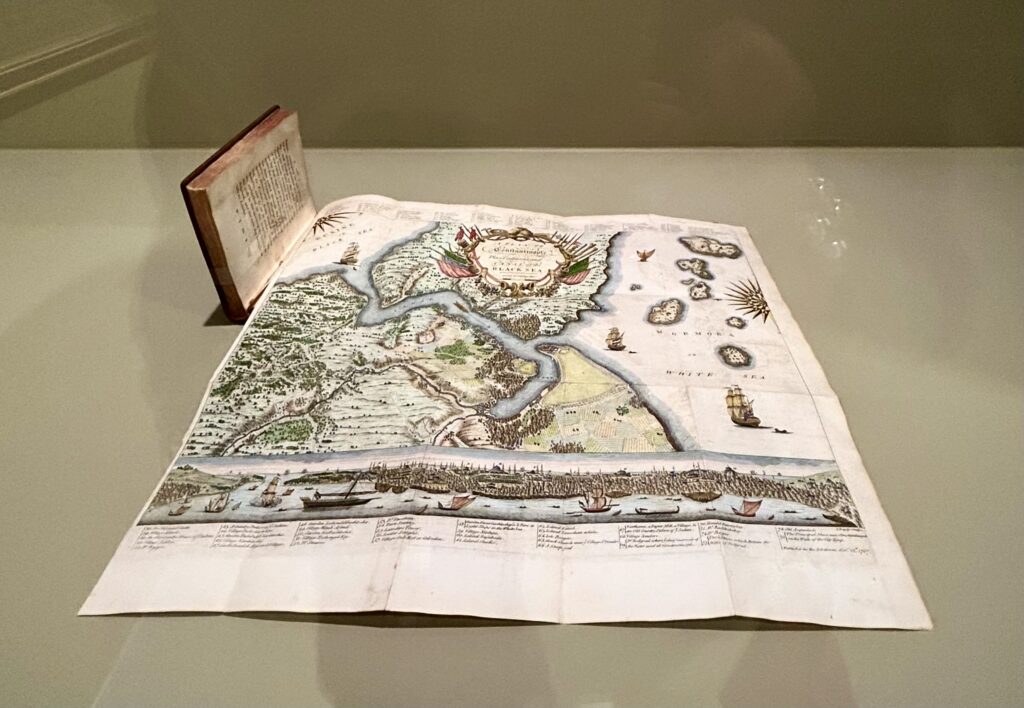

Confining ourselves to the emergence of Istanbul as a Greek city, one can see that the settlement retained its strategic importance throughout its subsequent Roman, East Roman and Ottoman eras. Throughout history it was a city coveted by many civilizations that belonged to different religions. Due to its unique geographic location, it was considered as the most important gateway, both in the north-south and the east-west directions. In addition to that, the topography of Istanbul, with the Bosphorus Strait, the Golden Horn, the Princes’ Islands, the green hills and the once flowing numerous streams indulged the viewer with a truly mesmerizing feast of scenery. Visitors were always attracted to the city. However, the interest grew even more when the city was conquered by the Ottomans, as a more eastern and Islamic culture became dominant, but at the same time, blended into the already existing, many-layered civilization. Over the centuries, Istanbul became a life-time destination for many, some of whom produced works that provide us with invaluable testimony to those times. This exhibition is important in allowing visitors, locals and foreigners alike, to see and reflect on some of those.

Woven, Textile (End of 19th-Beginning of 20th Century)

Amadeo Preziosi (1816-1882)

As the title implies, the time span of the exhibition is 500 years, starting from the conquest of Istanbul in the 15th century to the first quarter of the 20th century. The exhibits are produced by people from a variety of professions such as ship captains, soldiers, travellers, ambassadors, photographers, writers, architects and city planners. Most of them are foreigners from the West with diverse motives for depicting Istanbul. These may be political, military, aesthetic or personal record keeping. The medium that is used by each of them is also manifold and each of them is supposed to have served their purpose in their own way. Some of them reveal diplomatic while others disclose intricate personal relations. Through these, it is possible to track the major changes Istanbul went through over centuries as a multi-cultured and colourful society.

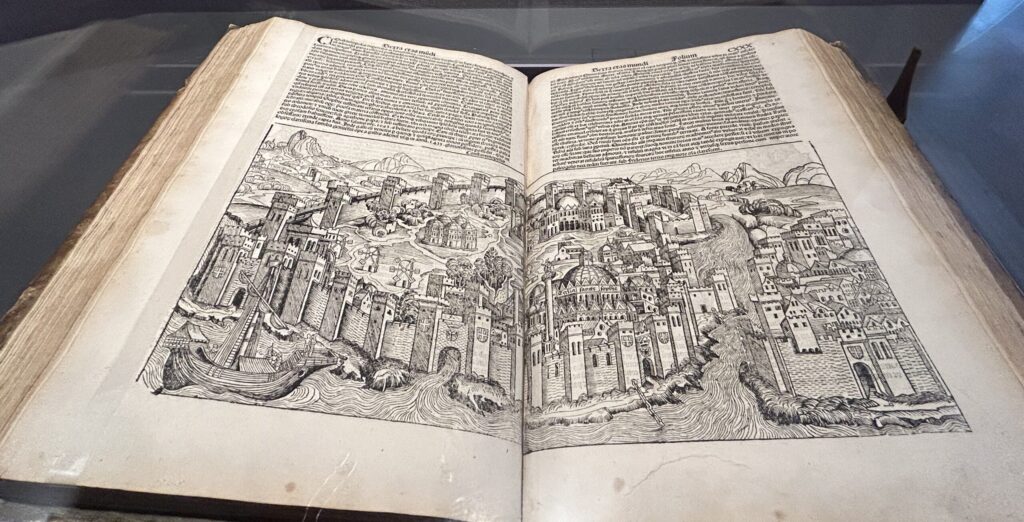

Written by Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514)

Illustrated by Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff

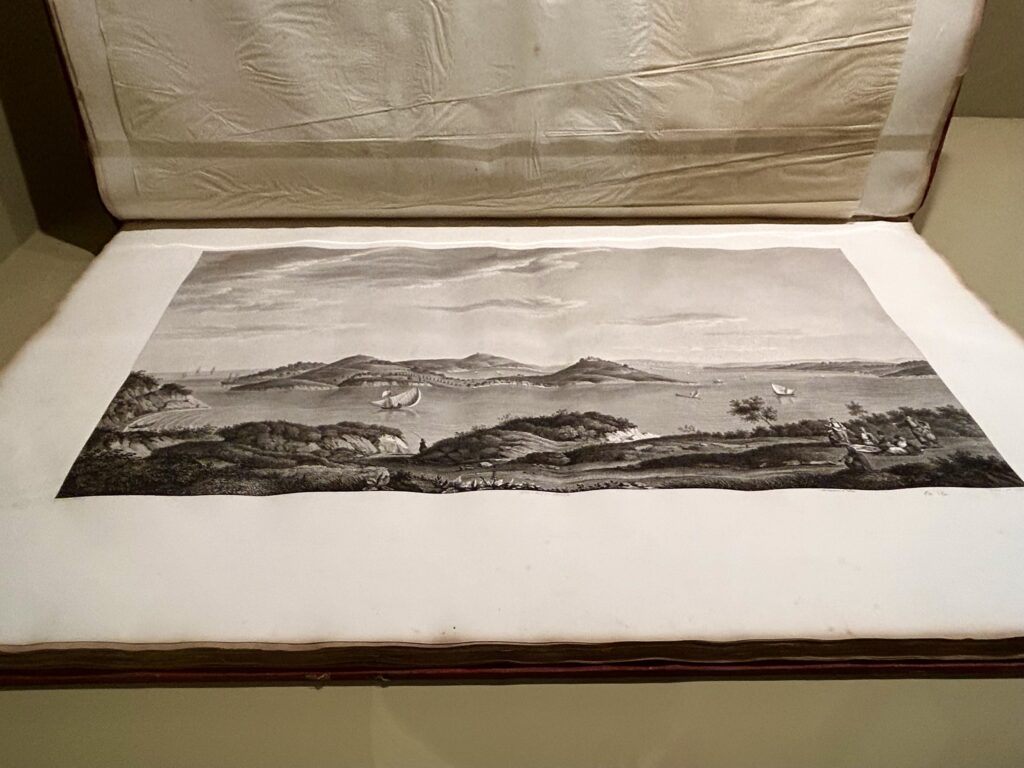

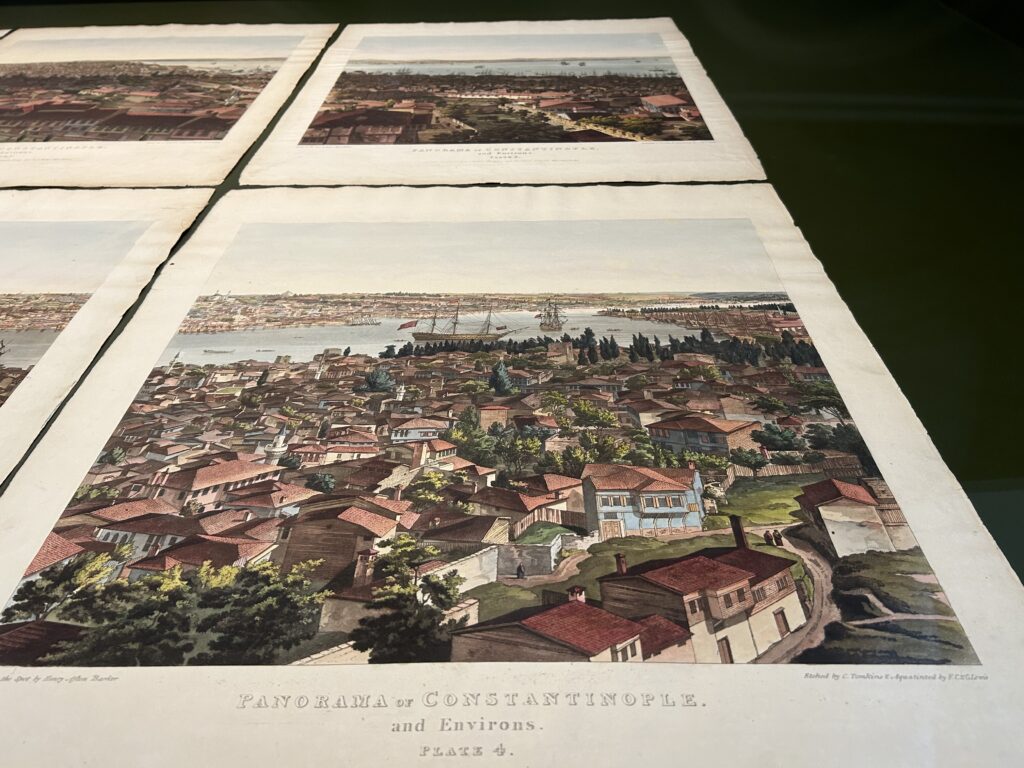

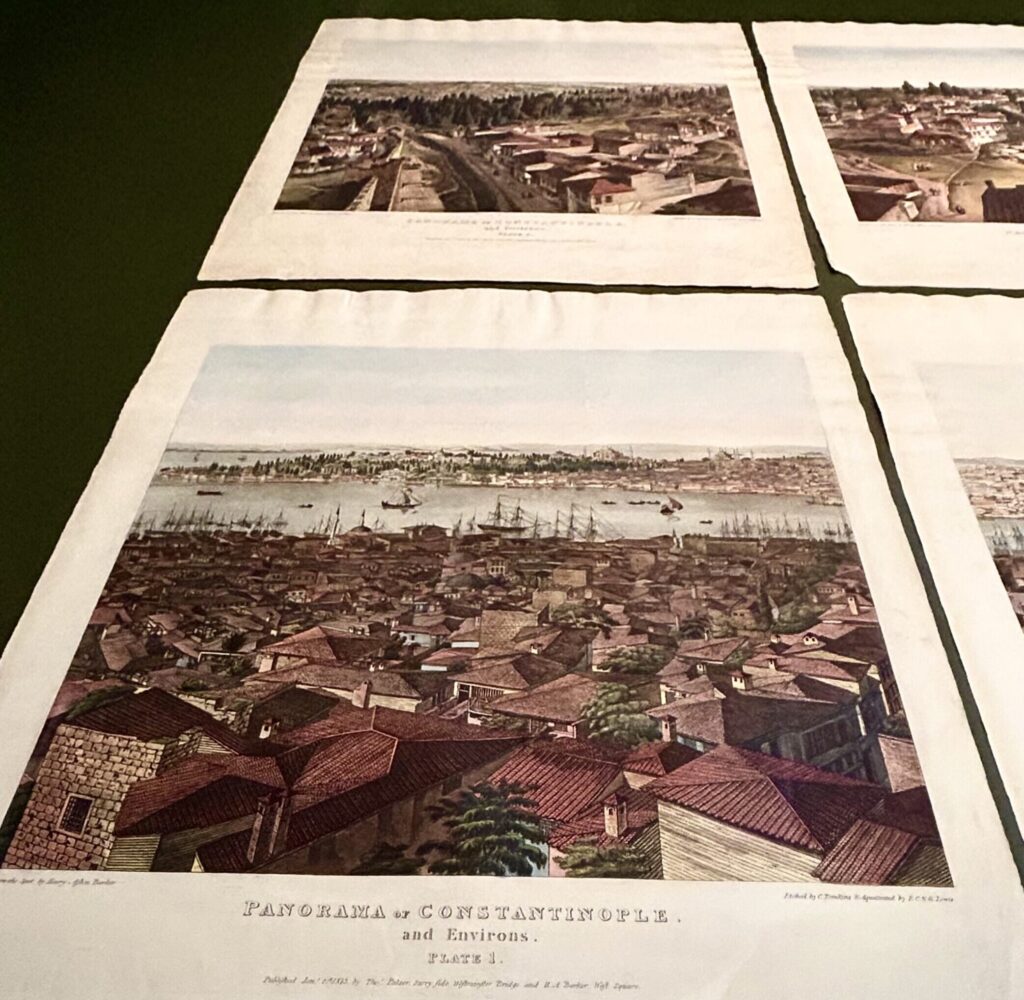

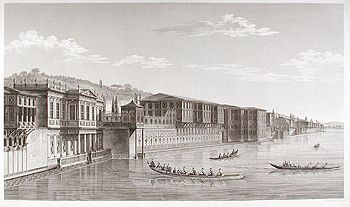

The oldest item in the selection of the exhibition is a book on Istanbul that was printed in 1493. The book by the name Liber Chronicarum (a.k.a. Nuremberg Chronicle) was written by Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514) and illustrated by Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff and their workshop. Another pioneering exhibit in its field is the panoramic photograph taken in 1857 by James Robertson who is said to be the first photographer ever to take scenic photos of the city. There is also Henry Aston Barker‘s (1774-1856) panorama of Istanbul that he painted from the top of the Galata Tower. The eight views beautifully depicted as a series by Barker were later etched by C. Tomkins and aquatinted by F.C. and G. Lewis in 1813.

Celebrated city of Constantinople and its Environ

Taken from the Town (i.e. Tower) of Galata (1813)

Henry Aston Barker (1774-1856)

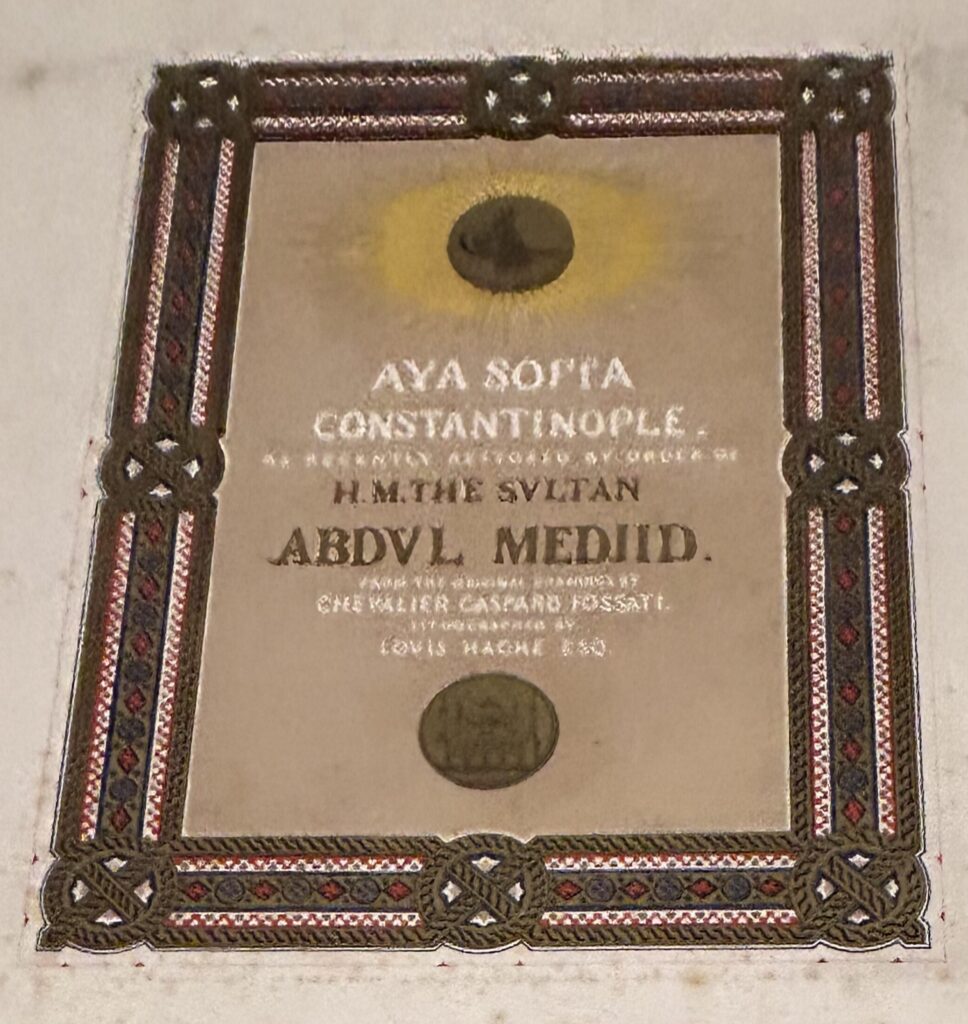

While visiting the exhibition, be sure not to miss any of the upper floors as they are full of invaluable items. Only very few of them have been hand-picked for this post. Among many, two deserve special attention in my view. First of these is an album of 25 drawings of the Hagia Sophia by the Swiss-Italian architect and artist Gaspare Trajano Fossati (1809-1883). Together with his brother Giuseppe Fossati (1822–1891), he came to Istanbul in 1837 where they completed more than 50 projects in twenty years. Their greatest work was the restoration of Hagia Sophia between 1847-1849 which was commissioned by Sultan Abdülmecid (r. 1839-1861). The album consists of drawings initially made by Gaspare Fossati and later lithographed by Louis Haghe. The prints were further hand-coloured and placed on card board.

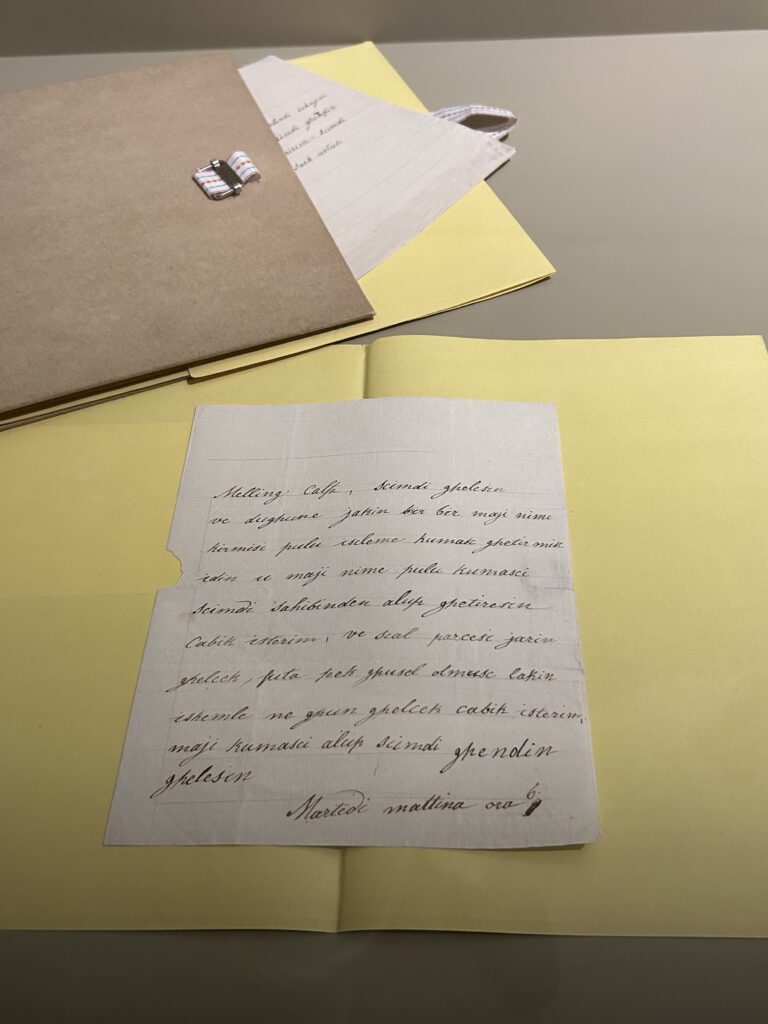

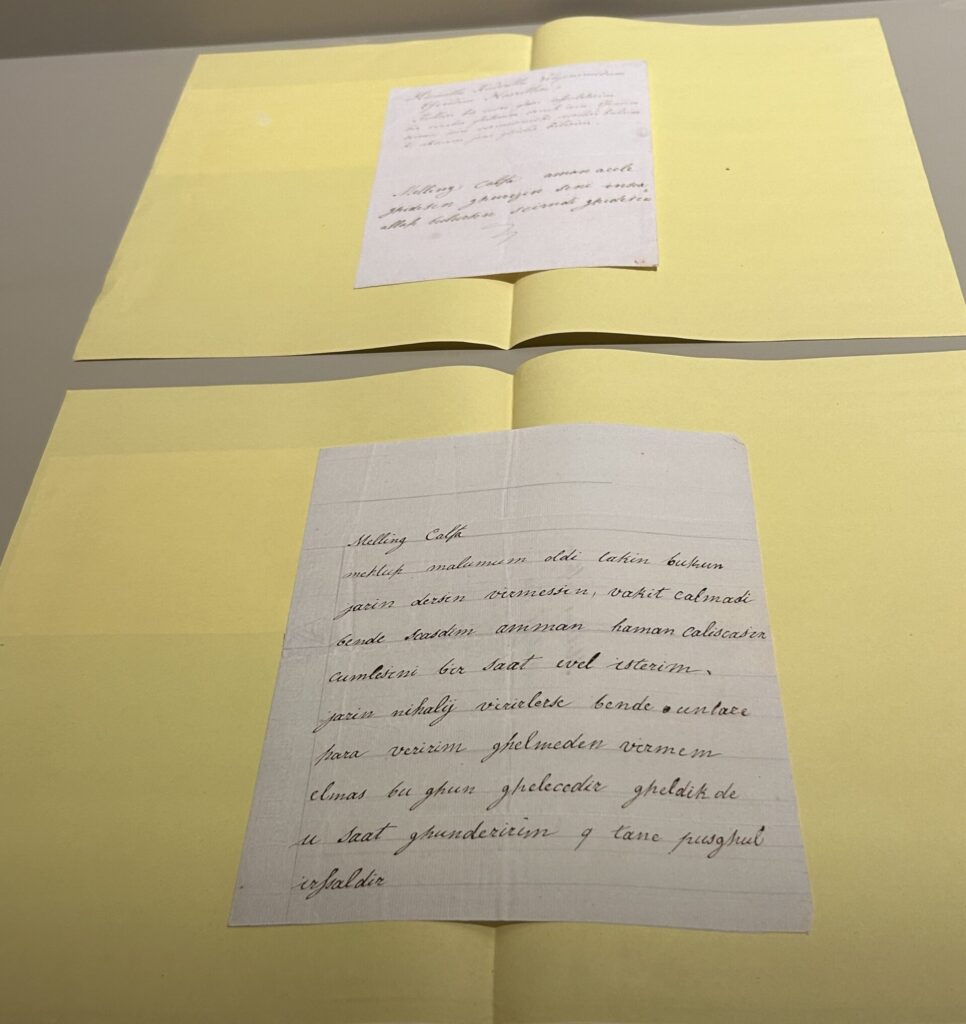

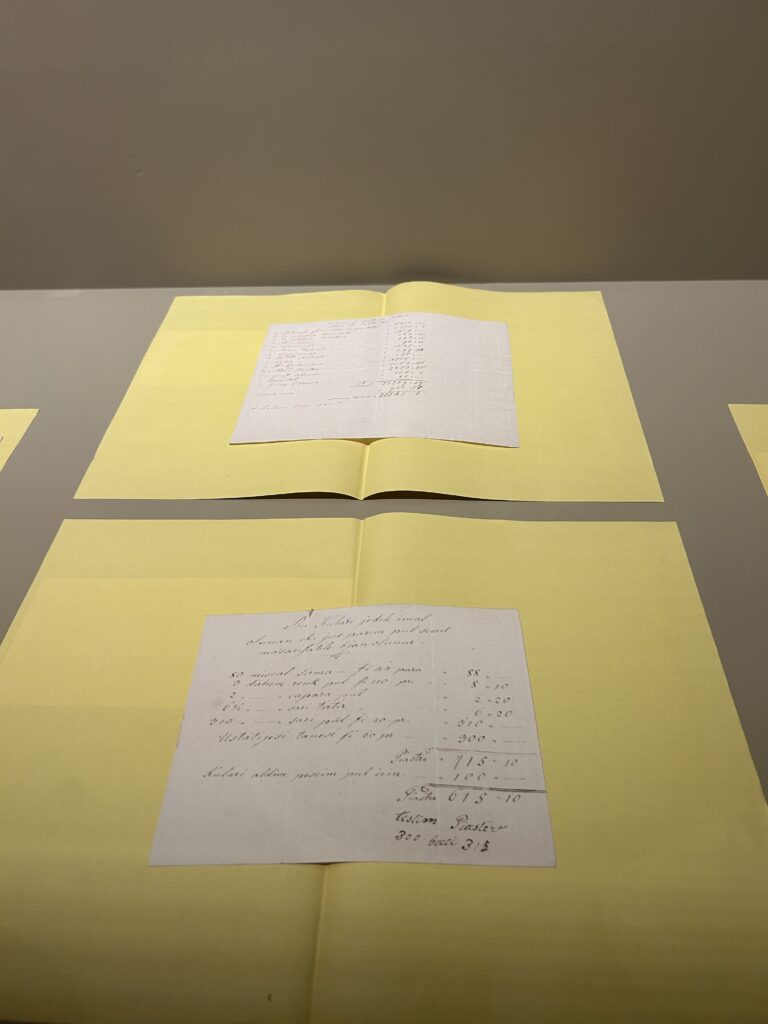

Antoine-Ignace Melling (1763-1831) is perhaps one of the most interesting and prolific foreigners who spent time in Istanbul. Born in Karlsruhe, Baden in Germany, he was the son of a sculptor. After his father’s death, he stayed with his uncle Joseph Melling who was a painter. Later he also studied architecture and mathematics, paving his way in becoming a renowned painter and architect. He started travelling at the age of nineteen, first to Italy and Egypt and then finally to Istanbul where he stayed for eighteen years. He initially came to Istanbul as a member of the Russian Ambassador’s entourage in order to depict pictures for some dignitaries and to decorate the winter and summer palaces of the embassy. He later became the imperial architect of Sultan Selim III (r. 1789-1807) by the recommendation of his half-sister and confidant, Princess Hatice Sultan (1768-1822). In 1795, Hatice Sultan commissioned a labyrinth for the garden of her palace in Ortaköy. The success of the garden brought further commissions by Hatice Sultan who asked Melling to initially redecorate her palace and later to build other palaces. Their relationship grew so intense that it is said Melling had a personal private apartment in the palace that was more luxurious than the private quarters of the husband of the princess, Seyid Ahmet Pasha. The Pasha was away most of the time and the marriage was in reality a political formality. Apart from architectural and decorational work, Melling also designed clothes and jewellery for Hatice Sultan. He learned Turkish and they frequently corresponded. However, he could not learn the Arabic letters that were used at the time. (Conversion to the Latin alphabet was realised in 1928, five years after the foundation of the Turkish Republic), So, the princess wrote her letters in Turkish but using Latin alphabet letters, more than one hundred years before the conversion of the alphabet in Turkey. Some of these extraordinary letters are on display at the exhibition. It is very exciting to observe these letters that at first sight seem to be written in a foreign language. But looking at them more closely as a native speaker, one realises that the princess uses her knowledge of the Italian language to be able to write certain Turkish words phonetically. In that way, she was able to write words comprised of sounds that do not correspond to a single specific letter in the Latin alphabet. For example, the word şimdi (now) in Turkish is written as scimdi, the word getir (bring) is spelled as ghetir etc.

Antoine-Ignace Melling (1763-1831)

Antoine-Ignace Melling

Source: www.wikipedia.org

During his long stay in Istanbul, Melling drew the most detailed depictions of Istanbul of that time. The Turkish Nobel Laurate Orhan Pamuk, a great fan of the artist, has reserved a whole chapter to Melling in his book ISTANBUL- Memories and the City where he writes how, starting from a very early age, he enjoyed spending hours looking at these pictures that were full of minute elements. Melling’s pictures are not just works of art but are also an invaluable source to the special characteristics of everyday life in the Ottoman Istanbul.

The exhibition at Meşher contains many more interesting items. The purpose of the present post is just to give a taste of the collection on display and the selection of the described articles no doubt reflects the subjective taste and interest of the author. There are many more waiting to be admired by others with different backgrounds and perceptions.

To share this post

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

About the author