The Greek city state of Byzantium (c. 658 B.C.-196 A.D.) was left in ruins for several years after it was conquered by the Roman emperor Septimius Severus. The city had become the object of the emperor’s wrath because Byzantium had chosen the wrong side a few years ago. Severus was one of the two contenders for the Roman throne when the previous emperor Pertinax was assassinated in 193 A.D. Byzantium had surrendered voluntarily to the forces of Severus’s rival Pescennius Niger. An act that could not go unpunished after Septimius Severus defeated Niger and killed him.

At the time, Byzantium was located on the First Hill of ancient Istanbul. The city was totally sacked and destroyed. It might have been abandoned by Severus had it not been for his son Caracalla, who convinced his father about the unique strategic importance of the city. Thus, Severus decided to rebuild the city on a larger scale and to surround it with new defence walls. This new city was to become at least twice as big as the ancient city of Byzantium.

(The reconstruction is taken from the Hippodrome Exhibition at the Nakkaş Cistern in 2015.)

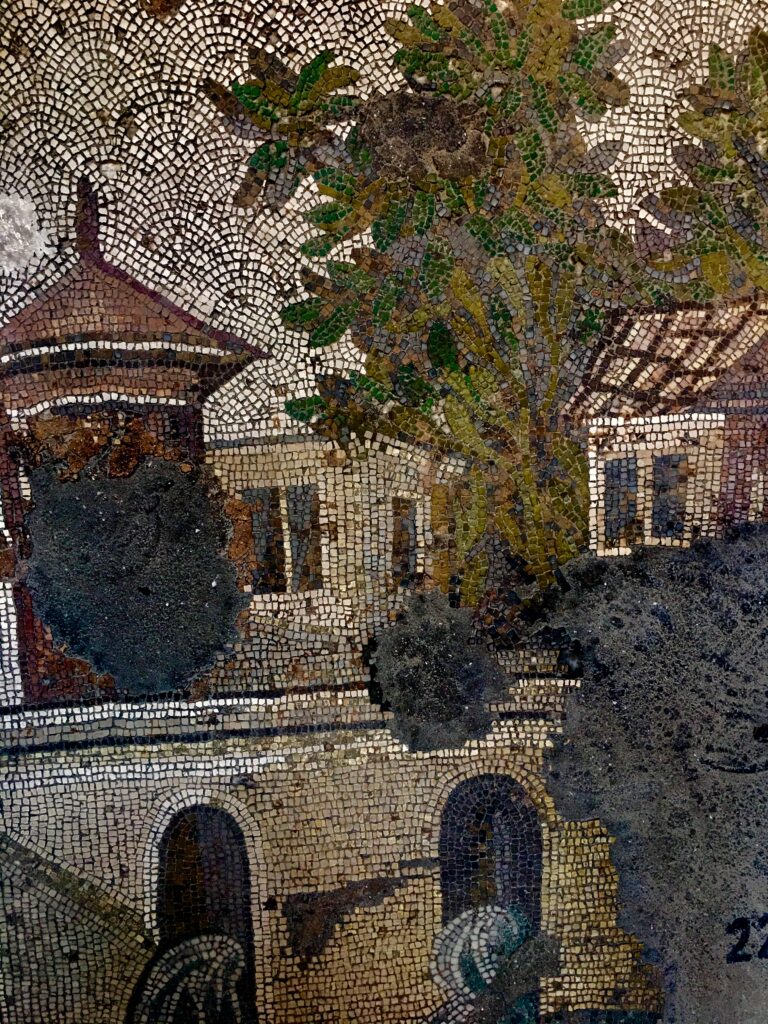

During the reign of Septimius Severus the city began turning into a majestic Roman city. The Hippodrome (situated where currently there is the At Meydanı, the square in front of the Blue Mosque), the Baths of Zeuxippus, the colonnaded avenue Mese (today’s Divan Yolu) running from the forum Tetrastoon (the great square in front of Hagia Sophia) to the summit of the Second Hill, temples for Apollo, Artemis and Aphrodite were some of his contributions to Byzantium. However, it took almost one and a half centuries for the city to become the stellar settlement of the empire.

Emperor Constantine reconstructed Byzantium when he decided that this city was to become the capital of the new Christian Roman Empire. During the reconstruction, he resided in Nicomedia (Izmit). In 330 A.D. the city was ready for its new role in history. From then on, Byzantium officially became NOVA ROMA CONSTANTINOPOLITANA, as it was engraved on a stela that was publicly set up in the Strategion (located where today there is the Sirkeci railway station.) This area was a military training ground since the earliest days of Byzantium and it was here that the imperial edict of the foundation of the city was placed. NEW ROME, THE CITY OF CONSTANTINE… In spite of the official name Nova Roma, the city became known as Constantinopolis in Greek from the very beginning. However, the natives of the city continued to call themselves Byzantini.

Since Byzantium was to be the new capital, the New Rome, it was evident that Constantine would commission a Great Palace in his city and he did. However, the palace was enlarged, rebuilt, restored and adorned several times by the succeeding emperors during the following eight hundred years. It was almost completely destroyed during the Nika rebellion in 532, but was rebuilt by emperor Justinian on a larger scale. The gardens and pavilions of the palace overlooked the Marmara Sea from the slope of the First Hill. The Great Palace consisted of several different establishments. These were, the Sacred Palace, the Daphne Palace and the Chalke Palace (located near the present site of the Blue Mosque); the Palaces of Magnaura and Mangana (located south-east of Hagia Sophia) and the Palace of Bucoleon which was a summer palace that looked down on the Harbour of Bucoleon, the small port of the Great Palace. There was also a special direct access from the Great Palace to the Kathisma (the emperor’s lodge) of the Hippodrome.

(The reconstruction is taken from the Hippodrome Exhibition at the Nakkaş Cistern in 2015.)

In its time, the Great Palace had no match to its splendour in the world. Foreign diplomats and travellers gave accounts of a palace rich with gold ornaments and beautiful mosaics. It was said that the ceiling of the throne hall was covered with gold. The emperors ruled the empire from this magnificent abode for nearly nine hundred years until the invasion of the city by the Latin Crusaders in 1204. The palace was plundered savagely like the rest of the city. There was hardly anything left after the 57 years long reign of the Crusaders. The Great Palace was never to return to its glamour and grandeur again because, in the following years Byzantine emperors preferred to reside in the Palace of Blachernae in the north-west corner of the city.

Eventually the Great Palace was reduced to rubble. It is said that, when Sultan Mehmet II conquered the city, he was extremely grieved to see this famous palace in such a state. As he walked through the great halls, he recited the verses of the Persian poet Saadi Shirazi (some sources attribute the verses to the Persian poet Firdevsi):

“The spider is the curtain-holder in the Palace of the Caesars

The owl hoots its night call on the Towers of Aphrasiab”

The yellow building with a tower at the back is the former Sultanahmet Prison, the current Four Seasons Hotel

The remains of the Great Palace were demolished in the following centuries. Some of the stones were used in the construction of the Topkapı Palace and other monuments. Part of it was demolished to clear space for the Blue Mosque. Excavations of different parts of the palace began in the 1920s. Between 1935-1938 a large excavation by the team of the University of St. Andrews revealed the beautiful mosaics that are today exhibited in the Mosaic Museum.

The Mosaic Museum is one of the hidden treasures in the vicinity of the Sultan Ahmet Square. It is situated in the Arasta Bazaar behind the Blue Mosque. The bazaar itself was part of the complex of the Blue Mosque. The shops were built in the 17th century to provide income for the upkeeping of the Blue Mosque (as was the tradition for nearly all significant mosques.) The bazaar was badly damaged due to a fire in 1912 but was restored in the 1980s. The entrance to the museum is inside the bazaar, among the shops. Previously, it was more difficult to find as the entrance could be barely distinguished between the two adjoining shops. Now, the location of the entrance has been slightly changed and it is more visible.

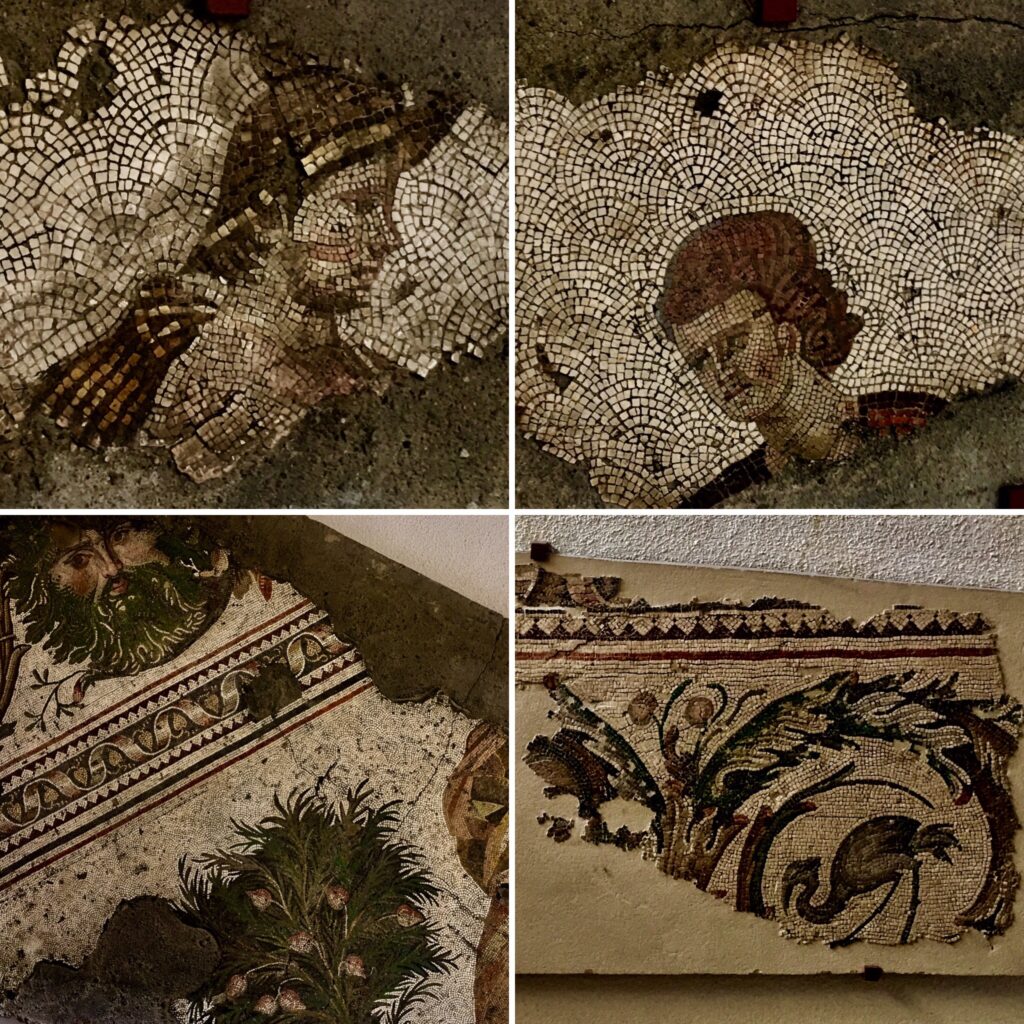

The columns, capitals and various architectural remains that were found in this location, in addition to the beautiful mosaics, are thought to be parts of the north-east portico of the Mosaic Peristyle. Thiswas a colonnaded walkway that presumably led from the imperial apartments of the Great Palace to the Kathisma of the Hippodrome. The 180 square metres of mosaics on display are only a portion of the whole structure. A much bigger part is thought to be under the surrounding buildings in the vicinity.

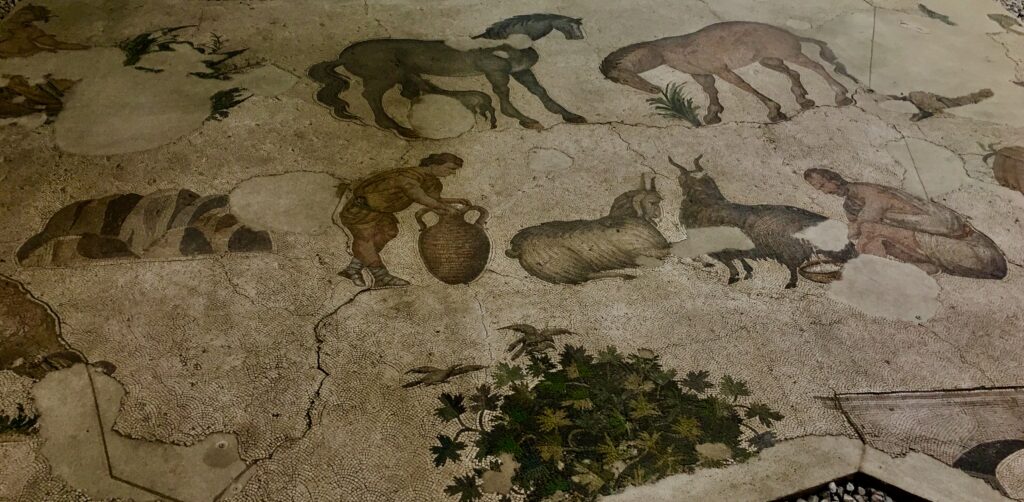

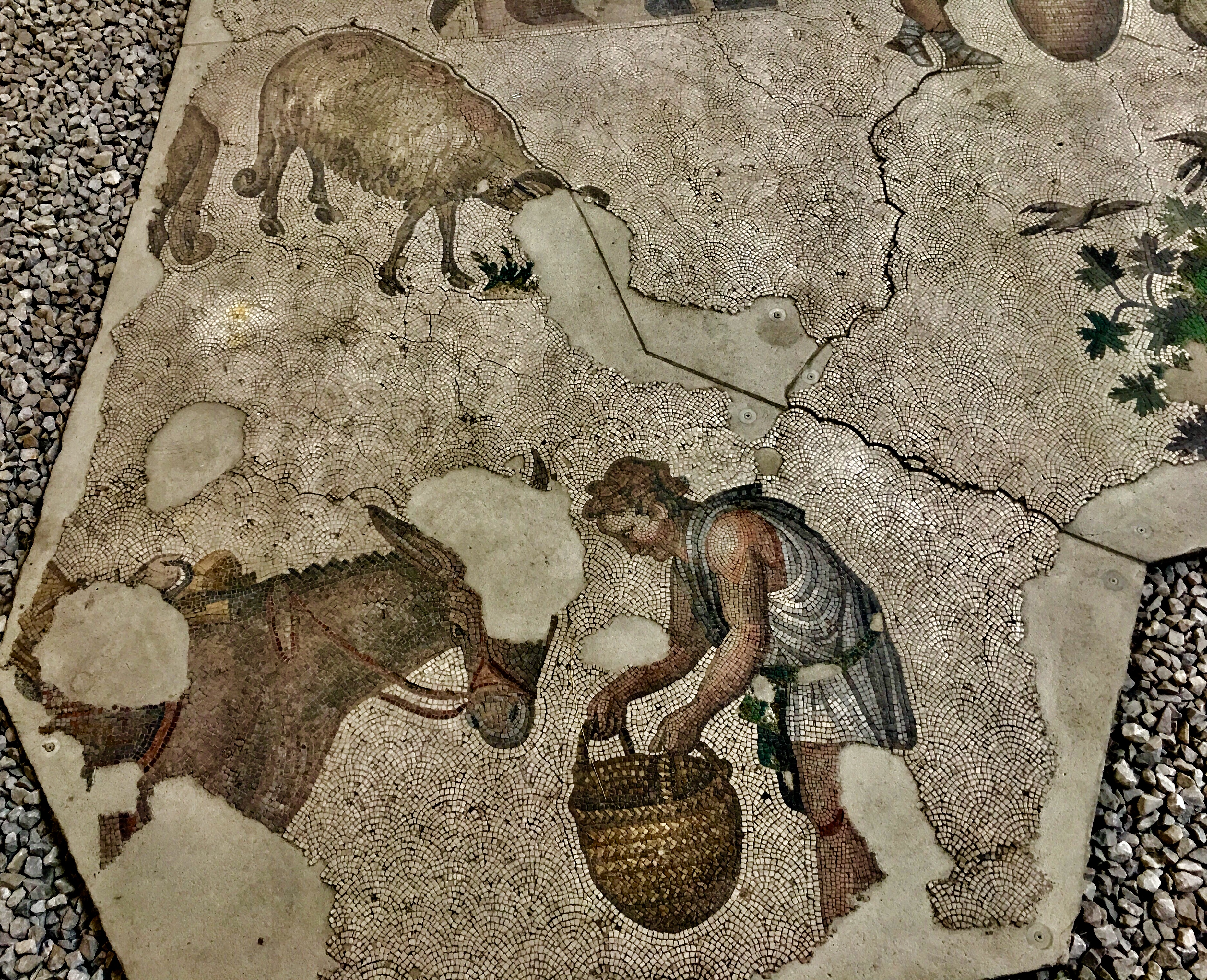

After years of controversy, experts finally agreed that the mosaics displayed at the Great Palace Mosaics Museum can be dated to between 450-550 A.D. These mosaics do not have religious depictions. They generally reflect scenes from everyday life which makes them all the more valuable as they provide clues about life in Constantinople in those days. Apart from these depictions, there are also illustrations of nature and mythological stories.

There are 90 different themes and 150 human and animal figures reflected in the mosaics. It is believed that, a large group of artists worked on them under the guidance of the leading masters of the era to create these beautiful works of art.

The mosaics are made of limestone, terracotta pieces and coloured stones with an average size of 5mm. Some of the outstanding scenes among the mosaics are a griffon eating a lizard, a mare feeding its colt, a man milking a goat, a man feeding his donkey, an elephant and a lion in a fight, a child herding geese. Looking at these wonderful mosaics, one can only wish that one day the rest of the mosaics will be excavated too.