Galata can easily be named as the oldest and most cosmopolitan part of the Beyoğlu district. In fact, for a very long time, it was the only settlement across the Golden Horn. Early settlements in this area date back to ancient times. The geographic location seems to have provided the area a special privilege in maritime trade since antiquity. However, it was during the Middle Ages that Galata became a rising star in Istanbul and the region. The area excelled in trade, banking and finance over time and preserved its importance in that respect, not only in Byzantine and Ottoman eras, but also for a long time after the foundation of the Turkish Republic.

Galata’s reputation declined as the economic and financial institutions moved out of the district during the last quarter of the 20th century. The once prosperous area with its Jewish, Armenian and Levantine upper class inhabitants, its blocks of Art Nouveau apartments, schools, and temples soon became run-down and derelict. Car repair and workshops of all kinds slowly took over historical buildings. Safety became a real issue and even Istanbulites preferred to keep away from Galata. The value and meaning of this incomparable heritage was perceived only at the turn of the millennium when major renovations in the area first started. Boutique hotels, bars, cafes, nightclubs and shops sprang up in the area. Thanks to these pioneers, Galata is once again becoming a popular district of Istanbul. There is still a long way to go to revive the district to the status it deserves but, the popularity it has gained over the past two decades is a sign of its future. Today, the Galata area is a major attraction point for visitors and Istanbulites alike. Just like the rest of Beyoğlu, there is plenty to explore. You can be sure that, at each turn, you will find something of interest and a glimpse of times centuries ago. (For more information about Beyoğlu and Jewish presence in Galata, you can click on the links.)

Across the Golden Horn (not visible in this photo), the Topkapı Palace (on the left), Hagia Irene and Hagia Sophia (on the right)

There are numerous theories about the origin of the name Galata. Some of them have been disproved by historical facts. Nevertheless, it is known that the district had several other names at different points in time. It is stated that the region was initially called Sykai by the Byzantines. First city walls around the area were commissioned by Constantine the Great (r. 306-337 A.D.) in the 4th century. Later on, it became known as Regio Sycena. It was Emperor Justinian I (r. 527-565 A.D.) who named the district as Galata in the 6th century.

(You can click on the link for more information about the mosque.)

Istanbul has been a locationwise strategically important city since antiquity. However, in Byzantine Constantinople the city also acquired an invaluable position in world maritime trade and commerce. It stood at the crossroads of several trade routes that had been created by the development of maritime trade in the Middle Ages. The Italian city states of Genoa, Pisa, Amalfi and Venice were the main actors of this prosperity and they quickly realised the importance of the city in that respect. They developed close relations with the Byzantine Emperors and obtained important privileges, including settlements in the city as early as the 10th century. The Genoese were the latest in establishing such relations but this did not hinder their settlement in the Galata area. Moreover, in time, they created here a “Genoa away from Genoa“. Almost a replica of their home city with similar houses, wide staircase streets and monuments.

There was a time, during the Latin Conquest of Constantinople between 1204-1261, when the Genoese lost their advantageous position in Galata. Having led the Fourth Crusade to Constantinople, the Venetians gained power and exploited it to its full extent. Galata became a Venetian district. The Genoese were only able to regain their previous status after the invasion ended. The Treaty of Nymphaeum (1261) allowed the Genoese to found trade guilds and build palaces, churches, houses, baths, bakeries and shops. They were also given the right to free trade. In 1304, they built a fortification around a rectangular area by the Golden Horn that today corresponds to the strip between the two bridges. Namely, the Galata and the Atatürk bridges.

Having regained full authority and control, the Genoese started building walls around an area that was much larger than before. In fact, it took them several phases in time to enlarge Galata. In 1446 it reached its final dimension. The district was eventually surrounded by the Genoese walls and there was also a moat that bordered the outer wall. Galata now resembled the Italian cities of the era by the Mediterranean. These walls stayed almost in tact until 1870. They were mostly damaged later on, due to fires and earthquakes. Some sections of the walls are still visible in the area. You can observe them mostly in the vicinity of the tower. They are either in open air or inside the buildings that have been built later.

The Galata Tower was erected in 1348 as a part of the first expansion of the colony. It was the apex of the fortifications, standing at the highest point on the topography. The tower was initially named as Christea Turris (Tower of Jesus). After the Ottoman conquest, it was used for various purposes such as military storage, dungeon for prisoners and fire tower. In the 16th century, it was used as an observatory by Takiyyuddin bin Maruf-i (1526-1585) who was appointed as chief astronomer by the Sultan. Takiyyuddin was a mathematician, astronomer and engineer. The Galata Tower is also closely related to a historical figure, Hezârfen Ahmed Çelebi (1609-1640), in the minds of Turkish nationals. Hezârfen (meaning polymath) Ahmed Çelebi was an Ottoman scientist who was determined to fly. He built a hang-glider and, after several practices elsewhere with eagle wings, flew from the Galata Tower. It is said that, using the winds, he landed in Üsküdar. Sultan Murat IV, who watched him from the Old City, rewarded him with a pouch of gold. Nevertheless, he considered Ahmet Çelebi as a dangerous man who could be capable of doing anything. For that reason he was exiled to Algeria where he died at a young age.

Today, the Galata Tower offers visitors a great view of the Old City, the Golden Horn, the Marmara Sea, the Princes’ Islands and the Bosphorus. I definitely recommend sparing some time for the experience. The view is not only beautiful from up there, but it also allows the visitor to have a better understanding of the layout of the city as well. You will be amazed to see how certain places actually are within a short distance from each other around Karaköy, Tophane, Galata, Beyoğlu and the Old City. The tower is open between 08:30-24:00. You can avoid crowds and long queues if you go early. The peak hours are naturally towards sunset hours. No doubt the view is spectacular with the sun setting behind the Old City. However, you can enjoy almost the same view from most of the rooftop restaurants in the area.

When the Ottoman’s conquered Constantinople in 1453, the Genoese handed over Galata to the Ottomans and they became the subjects of the empire. On the other hand, the area continued to be the heart of finance, banking and trade with its cosmopolitan population, even though some parts were populated with Muslim subjects as a deliberate policy of the state. The Galata bankers became increasingly important for the Ottoman court after the Treaty of Karlowitz (26/1/1699) which marks the beginning of the recession period for the Ottomans. Loss of major territories in Europe where they had expanded for centuries brought a great financial crises upon the Ottomans. The state became increasingly reliant on credits that were provided by the major financial actors in Galata.

the Galata Tower

Coming down from the Galata Tower, you can spend a pleasant time exploring the area. Galata has plenty to offer in that respect for eyes that can see and for those who are interested. You will almost immediately encounter a very elegant fountain in Ottoman style which is incorporated in the remains of the Genoese defence wall behind the tower. The fountain has beautiful engravings of various fruit and flowers on its marble background. It was built in 1732 and is considered as a superb example of Tulip Era (1718-1730) art even though it was built right after that period. (For more information about the period, you can click on the link.) Take some time to observe the figs and the pears in the bowls, the flowers in the vases and the cypress trees. The name of the fountain, Bereketzade Çeşmesi (Fountain), causes some confusion because it was originally built as a part of a mosque by the same name at a much earlier date. The Bereketzade Ali Efendi Mosque, which you can see further down the slope to Karaköy, was the first mosque that was built in Galata after the Ottoman conquest in 1453. Hadji Ali Efendi, who was the first Ottoman commander of the Galata Tower, commissioned the mosque during the same year and also undertook the role of imam for a while. A fountain was built on an outer wall of the complex, as was the tradition of the time, that came to be known as the Bereketzade Fountain. However, both the mosque and the fountain were reduced to ruins and repaired several times during the course of history. The fountain took its current form during the reign of Sultan Mahmut I (r.1730-1754). In 1957 it was moved to its present location. The mosque had already been previously demolished. It was reconstructed according to its original plan in 2006, but the above-mentioned fountain was left by the Galata Tower.

As you will notice, the tower and the cafes and restaurants in its vicinity are the main attraction points in the district. The crowd in the area can at times become truly hard to cope with. Then you can step into side streets that are full of surprises. Galata is rich in satisfying your appetite to explore other historical places on your own. Here is a proposed route for you that I recently followed. You can be sure that there are plenty of others.

The Galata Kulesi Sokağı (Street), near the entrance to the tower, is a long and winding street that goes down to Karaköy, by the Golden Horn. Taking this street, you will soon see the Nardis Jazz Club on your right. The renowned club that opened its doors in 2002 has been hosting foreign and local jazz artistes for twenty years. It is housed in a historical building that is dated to the Genoese era of the district.

The tower underwent several renovations throughout history. One of them was at the time of Sultan Mahmut II (r. 1808-1839). That is why the eulogy above the doorway is thought to have been dedicated to him.

Furtherdown, the first street on your left is the Bereketzade Cami Sokağı (Street). Entering this street, you will see the previously mentioned Bereketzade Ali Efendi Mosque on your left. The mosque now has a much more modest fountain after being reconstructed. According to the explanatory plaque on the building, there exists a secret passage that connects the Galata Tower to the minaret of the mosque and then goes down to the old harbour in Karaköy.

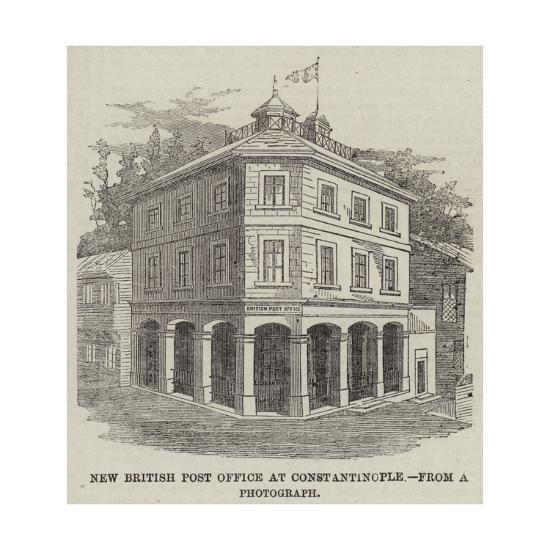

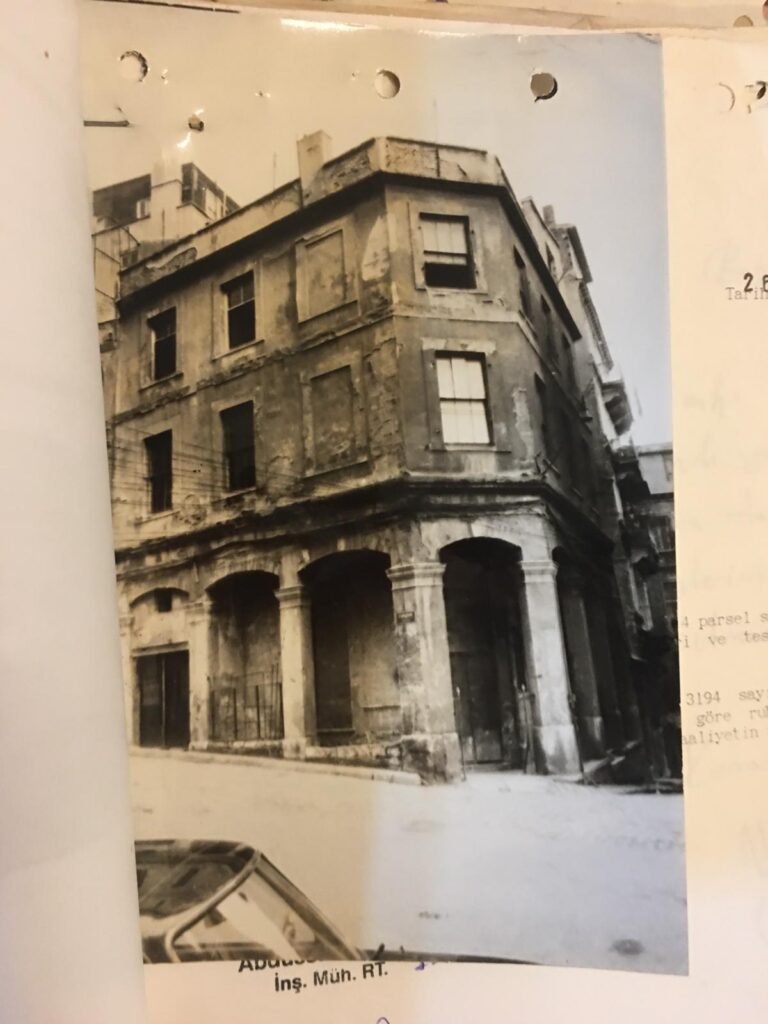

The white building at the corner on the right-hand side is the old British Post Office.

In the same street, on your right, there is a building which most probably caught your eye from the Galata Tower as well. There is no way you will miss it now either. This was once the British Seaman’s Hospital. Initially, there was another hospital building at this location which was built in 1855, during the Crimean War. The hospital was financed by the British government and served British officers and soldiers who fought at the front in Crimea. The hospital continued its operations, serving the personnel of British trade vessels operating in the region. Later treaties allowed Swedish and Norwegian naval staff to be treated as well. In 1904, the building was rebuilt in its current structure. It is the work of art of the British architect H. Percy Adams (1865-1930). The building is majestic in a style that is described as Art Nouveau with Gothic traces. It has a high rising tower that is said to have been built specifically for the sight of a billowing British flag in Istanbul. You can walk around the corner to fully see the structure. The hospital was under British administration until 1924. It was later transferred to Turkish Red Crescent and eventually to the Istanbul Municipality. Between 1937-1948, it served as a Rabies Hospital. Currently, it is an Eye Hospital.

This hospital is not the only British remainder in the area. At the diagonal corner from the hospital, across from the Bereketzade Ali Efendi Mosque, you will see a newly renovated building on which is written Postane. The building was inaugurated in 2021 as a cultural centre but, it was originally the British Post Office that operated during the Crimean War. At the time, there was another building at this location that provided postal service for British soldiers and officers. After the war, it continued its operations for civil and trade purposes. The present building was built in 1859 by the architect and civil engineer Joseph Nadin and was used as such until the post office was moved to a new building in Karaköy, in 1895. Between 1905-1912 it was used as the English High School for Boys. The school later moved to Teşvikiye. The function of the building changed several times as it changed hands over time, increasingly deteriorating until it was run down. The recent renovation is a good example of the struggle to save historical buildings and put them in alternative uses in Istanbul.

The Bereketzade Ali Efendi Mosque on the left, the British Post Office on the right corner.

Source: www.herumutortakarar.com

Source: Yaşar Adanalı at www.herumutortakarar.com

Although going down towards Karaköy along the Bereketzade Medresesi Sokağı (Street) offers no less interesting sights, I recommend you to leave that for another excursion and return to the Galata Kulesi Street; the street that we were following until we turned left to see the mosque and the hospital. Resuming your downhill steps, before long you will see another renovated structure on your right-hand side. This is the Ecole St. Pierre Hotel and its restaurant Il Cortile. The Italian restaurant Il Cortile is a pleasant addition to Istanbul’s social life and having tasted the food, I can recommend it for a light lunch or dinner. The atmosphere of the courtyard, as the name implies, is relaxing and peaceful after the commotion that goes on in the streets outside. The ambiance might be even better in the evening. Going to an Italian restaurant instead of a local one in Istanbul might seem odd but, being in the Genoese Quarter of long ago times, makes an Italian restaurant here more relevant than any other part of the city. You might prefer a short break at this restaurant before continuing your walk down to Karaköy. Or else, you can walk down and come back up here as we did. However, I must warn you that the climb back up is, maybe not impossible, but tedious. I would not recommend it in hot weather. If you do go to this restaurant, do not forget to have a look at the remains of the Genoese Fortress Walls inside. The nearly 1000 years old walls have been beautifully restored and renovated.

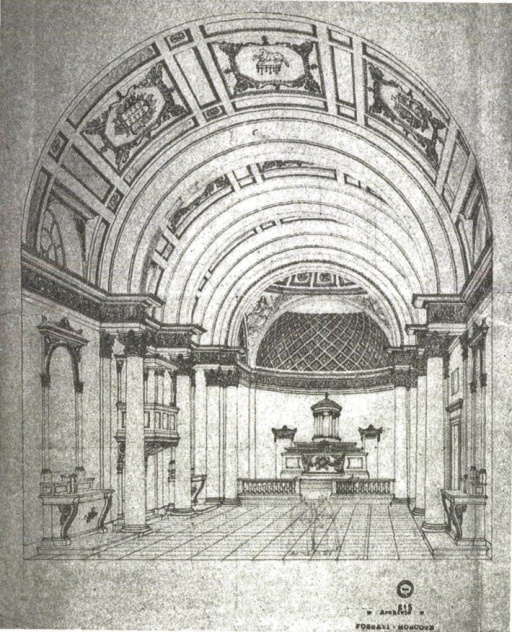

The building of the Ecole St. Pierre Hotel and Il Cortile restaurant deserves some attention. The territory is part of the large premises of the Saint Pierre and Paul Church and Convent. You will come across the church (a.k.a. Chiesa dei Santi Pietro e Paulo in Galata) on your right while you continue to walk down. As the street naturally winds to the right, the difference in altitude will allow you to see the roof of the church beyond the high wall. Entrance to the church grounds is also at this point. The door is closed but a poster announces that on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays there is free entry between 14:30-17:30 to The Fossati Brothers Exhibition. The place has close ties to the Fossati Brothers as will be explained shortly.

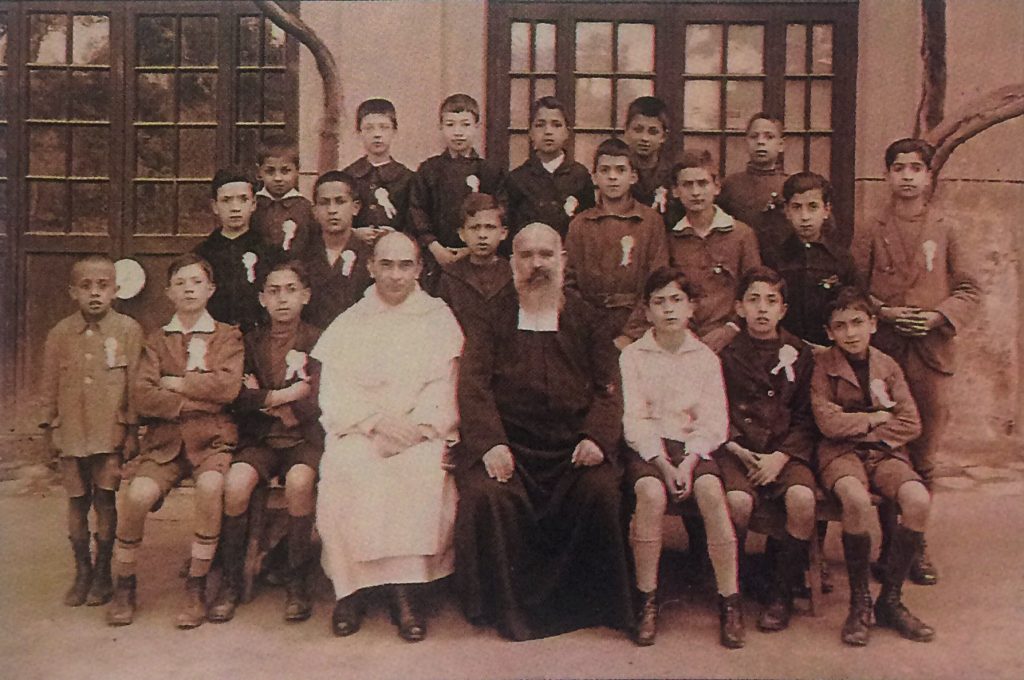

The Catholic congregation existed in Galata since the 13th century. There was an Italian Dominican church and monastery on this site since the late fifteenth century. The wooden structure suffered from two major fires in the district, in 1660 and 1731. Following the two drastic catastrophes, the church and the monastery were rebuilt in 1841 by the Swiss Italian architect Gaspare Trajano Fossati (1809-1883). The complex was later taken under the protection of France but, the school of the convent, Collège des Frères St. Pierre Elementary School (1842), continued to be administered by Italian Dominican priests. On the other hand, similar to other French missionary schools founded in Istanbul during the nineteenth century, the official language at the school was French. Education in the St. Pierre Elementary School was disrupted between 1914-1918, due to the First World War, until it was resumed in 1919. Although student enrolment never reached the pre-war numbers again, education continued until 1935. The waning number of students obliged the convent in 1922 to lease parts of the school as production facilities and workshops. One of these was a printing house on the ground floor of the building for a while. Today, the stone prints that belonged to this printing house can be seen at the reception of the hotel. Part of the school building that is now home to the Il Cortile restaurant is stated to have once been the place where the church choir used to practice.

Source: www.estphotel.com

was run by Dominican friars

Source: www.estphotel.com

Source: www.estphotel.com

Resuming our downward stroll, you will soon see the Galata House Restaurant on the left. This building was constructed in 1904, together with the British Seaman’s Hospital nearby. Between 1904-1919 it was used as the civil prison of the British empire in Istanbul. It was later used as the British military police station and intelligence centre during the occupation years of Istanbul (1919-1923) by Britain, France, Italy and Greece. After the Turkish War of Independence and the declaration of the Republic, the British continued to use the building for lodging purposes for members of the diplomatic corps until it was sold in 1933. Several changes of hand also caused changes in the use of the structure from lodgings to production facilities. In 1991, it was bought by the Göktuğ couple who are also currently running the restaurant. Being architects, they spent much time improving the physical condition of the building while, at the same time, trying to reveal the original layers of paint on the walls. Getting rid of about 20 layers brought to light the original drawings and writings of the British and Ottoman prisoners who were incarcerated here a century ago.

Turning into the next alley on your right (Eski Banka Street), you will see the colossal building of the Han of St. Pierre. A han is an Ottoman Turkish building that can be at times a traditional hotel (with or without a stable), a warehouse, a wholesale sales shops facility or a combination of these. In more recent centuries, the term was also used for a building of offices. St. Pierre Han is an important historical building in Galata that deserves to be taken care of. After years of neglect, luckily it is currently undergoing a thorough restoration by the Metropolitan Municipality of Istanbul. The first time I saw St. Pierre Han was in 1987. It was in a pitiable condition with terribly dirty car repair shops on the ground floor. However, it stood out proudly even in that condition, defying the centuries that it had witnessed since its erection in 1771. A marble plaque stood out on its facade. It denoted that it was the birth place of the French Revolution’s renowned poet André Chénier (1762-1794). The plaque was placed here by the Ottoman- French architect Alexandre Vallaury (1850-1921). Actually, he was not born in this exact building but, in an earlier wooden one that stood in its place. His life had begun in Constantinople but ended tragically at the guillotine by the order of Robespierre (1758-1794), who himself shared the same fate three days later.

Above, between the two windows, the plaque indicating that André Chénier was born here.

The initial building on this site was built in 1732 as the trade office and lodging of the French Embassy. This was why Chénier was born here. His father was a member of the French diplomatic mission in Istanbul. When the building burned down in 1770, St. Pierre Han was commissioned in its place the following year by the French ambassador Comte de Saint-Priest. The name of the building was inspired by the above-mentioned church and convent in the vicinity. The coat of arms of Saint-Priest and of the Bourbons are also on the facade of the building although currently none of the plaques are visible due to the scaffolding. Hopefully, all three plaques will be cleaned and visible after the restoration. The first official Ottoman state bank, Osmanlı Bankası, was founded in St. Pierre Han. In later years, the structure hosted the offices of important Levantine architects such as Hovsep Aznavur(1854-1935), Antoine N. Perpignani (1843-1905) and Giulio Mongeri (1875-1953).

It is practically possible to wander around for hours at you leisure and to discover interesting places at each step in Galata. I certainly would have done that if I hadn’t had a pre-set destination on my mind. So, instead of following the L shaped Eski Banka Street, that leads to the famous Bankalar Caddesi (the Avenue of Banks), return to the Galata Kulesi Street and continue down towards Karaköy. This route will also lead you to the Bankalar Caddesi which you will cross. Once you have done that, you will notice that the name of the Galata Kulesi Street will change to Perşembe Pazarı Caddesi. As the name implies, once there must have been a market on Thursdays at this location. Proceed down the hill without heeding a dead-end street and several alleys on your right until you reach the Galata Mahkemesi Sokak (the Galata Courthouse Street). We will turn right into this street. The street takes its name from the ancient building at the corner. It was built by the Genoese as a courthouse and used in that capacity until the end of the Ottoman period. Now, facing the courthouse building, there is a restaurant, Mahkeme Lokantası (Courthouse Restaurant) at the opposite corner. I haven’t personally tried the place but have read positive reviews about it on social media. Looking through the windows, the atmosphere seemed warm and welcoming with the white tablecloths.

The Arab Mosque (Arap Camii) in the Galata Mahkemesi Street is worth a visit. Just walk on once you have turned the corner from the Perşembe Pazarı Avenue. It is a huge building that would have been more visible if it were not surrounded by other buildings. There seems to have been such an effort at the end of the seventeenth century when the Sultan of the time ordered the demolishment of the houses in the vicinity. The structure of the mosque, especially the square minaret, is a clear clue for the true origins of the building. You will have the immediate impression that it is more like a church than a mosque. You are right. The Arab Mosque was indeed an earlier church.

Adile Sultan, the daughter of Sultan Mahmut II.

There are several tales concerning the origin of the name of the Arab Mosque. According to the most widespread one among these is the one that relates the mosque to the Umayyad siege of Constantinople between 716-717. Supposedly, it was built (with the permission of the Byzantine Emperor) on the foundations of a church by the Umayyad commander Mesleme Bin Abdülmelik. Hence, it acquired the name Arab. However, experts in the field have proven that this cannot be correct. It is stated that the name is probably due to a colony of Moors who had recently been expelled from Spain and were settled in the district early in the sixteenth century.

The exact date of construction of the original church is not known. Some sources state that initially there was a church by the name of Hagia Eirene here, built in the sixth century. A Catholic church dedicated to St. Paul was later built on top of it during the Latin invasion (1204-1261). These parts of the history of the place is controversial. However, it is stated with certainty that the church was taken over and rebuilt in its current plan by the Dominicans between 1323 and 1337. It was dedicated to St. Dominic. It was converted to a mosque in 1475.

There are two rooms that are on both sides of the mihrab. This is considered as another clear sign that the structure was once a church because no mosque has such rooms next to the mihrab.

The Gothic building of the Arab Mosque was burned, damaged and restored several times throughout its history. One of the major restorations was between 1913 and 1919 when a considerable number of Genoese tombstones, dated to the fourteenth and early fifteenth century, were discovered. These were transferred to the Archaeological Museum.

Ending this tour at the Arab Mosque is an option. Having a quick look at the only remaining gate of the medieval Genoese Galata town is also recommended. The gate is called Yanık Kapı (Burnt Gate) and is in the street by the same name (Yanık Kapı Sokağı), not far from the mosque. You will see the Genoese coat of arms above the archway. Afterwards, you can either stay around Karaköy or go back up the hill for a pleasant meal at the Il Cortile…