Istanbul is a city that offers the excitement of unexpected discoveries in its least imaginable corners. Enter a quite ordinary looking street and suddenly a breathtaking view of the Golden Horn, the Bosphorus, the Marmara Sea or the Princes’ Islands will offer a memorable feast for your eyes. Just when you feel suffocated by the ugly modern buildings and skyscrapers surrounding you, a centuries old historic monument will wink at you with serene wisdom. Trapped in a part of Istanbul that was almost empty twenty-five years ago, but is now where the concentration of high-rise buildings is the most, The Maslak Royal Lodges (Maslak Kasırları in Turkish) are a perfect example. These beautiful pavilions from the 19th century are remainders from the times when the area was covered with thick forests and a few farms at the outskirts of Istanbul. Today, the district is under the siege of the insatiable greed to create a surplus value from land and real estate. This is also where at certain hours the traffic can be a nightmare for Istanbulites commuting to and back from work. The good news for tourists and Istanbulites who have spare time to visit is that the Maslak Royal Lodges are easily accessible by metro. The beautiful pavilions are about 100 metres walking distance from the Atatürk Oto Sanayi stop on the Yenikapı-Hacıosman metro line.

The Maslak Royal Lodges consist of three pavilions, a conservatory and auxiliary buildings that are architecturally outstanding Ottoman examples of the era. The complex was built as a countryside residence and a hunting lodge amidst the forests that used to stretch as far as the Black Sea in the northern part of Istanbul.

Urban development in Ottoman Istanbul evolved for centuries within the walls of the Old City, as it had before the conquest of the city by Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror in 1453. At the time, the favourite recreational areas for both the royal family and ordinary people were along the shores of the Golden Horn and the areas in the vicinity. Locations on the other side of the Golden Horn, across the Old City, such as Galata, Pera (today’s Beyoğlu and İstiklal Avenue) were the districts where foreigners, the diplomatic missions and the non-Muslim subjects of the empire resided. Following the move of the royal household from the Topkapı Palace to the Dolmabahçe Palace in 1856, during the reign of Sultan Abdülmecid (r. 1839-1861), the new urban focus shifted to the shores of the Bosphorus and the hills beyond. As the once small fishing villages on the coast became adorned with royal winter and summer palaces and pavilions, other affluent members of the society also started taking interest in these parts of Istanbul.

As a result of the above-mentioned relocation in the 19th century, sultans and their families began to prefer new recreational areas. Newly developed imperial parks and estates were adorned with pavilions and lodges designed for their day trips or overnight stays. The Maslak Lodges are a perfect example of these kinds of constructions. Although the first buildings were constructed at the time of Sultan Mahmut II (r. 1808-1939), the complex took its present structure at the time of his son, Sultan Abdülaziz (r. 1861-1876). In 1868, he allocated the lodges to his nephew, the future Sultan Abdülhamid II (r. 1876-1909). The young prince (şehzade) later bought a large farm in the area to be used for agriculture and husbandry. The pavilions remained in the use of Abdülhamid’s family after his ascension to the throne and even after his reign. In 1924, with the new Turkish Republic, the place was given to the military to be used as a preventorium and rehabilitation centre for patients with chronic pulmonary disease. It was turned into a museum after 60 years, in 1984.

The name of the area, Maslak, took its name from part of the water supply system of Istanbul which became an important concern as early as the reign of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566). Big investments were made at the time for the construction of reservoirs, aqueducts and other water systems to bring water from the Belgrade Forest into the city. The famous chief imperial architect Mimar Sinan was responsible for these ingenious projects. The maslaks, from which the name Maslak was deduced, were a system of water tanks and towers set at the junctions in the water channels that allowed water to be distributed among two or more subsidiary channels. Thus, the district got its name from a maslak in the vicinity.

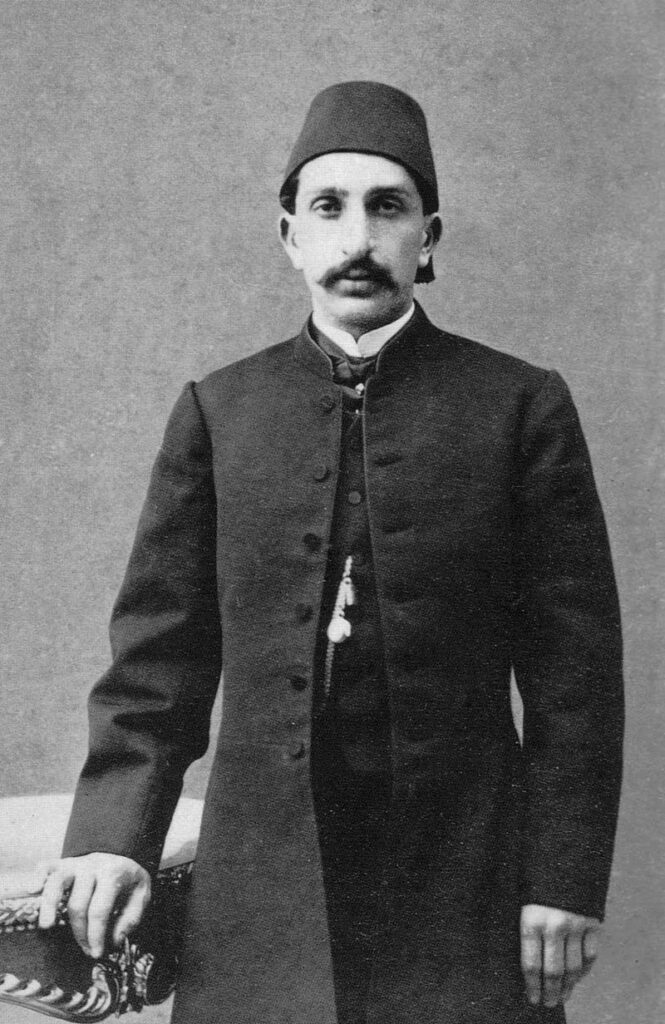

Before giving more information about the Maslak Royal Lodges, I believe the sultan whose name is closely linked to the place, Sultan Abdülhamid II, deserves a closer account. Sultan Abdülhamid was the 34th Ottoman sultan. One of the most unique features of the Ottoman empire is that, from its rise until its fall, it was ruled by 21 generations of a single (Ottoman) dynasty. Initially, the crown passed on to the eldest son as would be expected. However, at times there were uprisings and claims to the throne among siblings that led to long years of civil war. The most severe of these was among the sons of Sultan Bayezid I (r. 1389-1402). It lasted longer than a decade and the State almost collapsed. In order to prevent these kinds of struggles, Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror passed a law according to which, Ottoman sultans had their male siblings killed as soon as they ascended the throne. The practice continued for almost 200 years until the time of Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603-1617) who refused the massacre of his brothers. As a child, he had seen the 19 coffins of his uncles in the courtyard of the Topkapı Palace, while his father was enthroned. He was devastated at the sight and never forgot. When he abolished the law, confinement of princes to cages was brought up as a solution to prevent power struggles for the throne. A cage was a special section of the palace where the princes of the dynasty were kept under strict surveillance. It could be called a kind of house-arrest. They were allowed to have a limited number of concubines and servants. However, crown princes were not allowed to have children until they ascended the throne. This new procedure brought about a new system of enthronement. From the 17th century onwards, the eldest royal family member became the heir apparent which was not necessarily the son of the sultan. That is why, during the last centuries of the empire, there were often cases when the crown passed on to the brother of a deceased sultan instead of his son. For this reason, Sultan Abdülhamid II and his elder brother, Sultan Murad V (who was able to rule for only a few months), did not succeed their father (Sultan Abdülmecid) but their uncle, Sultan Abdülaziz did.

Sultan Abdülhamid II as a young prince

Source:www.wikipedia.org

The living conditions of the princes who were kept in their respective cages were always at the mercy of the ruling sultan. Being a very open-minded and liberal man, Sultan Abdülaziz did not restrict his nephews very much and allowed them to live outside the palace. He also took them to Europe during his trip in 1867 where the future Sultan Abdülhamid II was exposed to the European culture that he was already acquainted with by education. It was then that the young prince became fond of opera and theatre. So much so that, later when he was a Sultan, he had a private theatre built for himself at the Yıldız Palace where famous foreign opera and theatre groups would be invited to perform for him. The famous actors and actresses of the time such as the French actress Sarah Bernhardt and the Italian actor Ermete Novelli were among them. There was also a permanent group of Italian actors and actresses at the court during his time.

This photo was taken in London when Abdülhamid accompanied his uncle, Sultan Abdülaziz, on his tour to Europe in 1867.

Source: www.fikriyat.com

Abdülhamid II’s half-sister

Abdülhamid II was the son of Sultan Abdülmecid and a Circassian mother, Tirimüjgan. Some sources claim that she was Armenian. He was born in 1842 and was eleven years old when his mother died. The young prince and one of his half-sisters, Cemile Sultan (1843-1915), were raised by one of the other wives of their father. Both of them were very fond of their stepmother. During the reign of his uncle, Abdülhamid II initially lived in a pavilion in Tarabya, by the Bosphorus. When Sultan Abdülaziz was informed that his nephew was swimming regularly in the Bosphorus, which was very unusual in the royal family and considered to be dangerous, he forbade it and gave the Maslak Lodges to Abdülhamid II as a present. The Maslak Lodges became home to the young prince until his enthronement in 1876. During this time and later as a sultan, Abdülhamid earned a considerable amount of money at the European stock exchange markets and bought vast areas of land in various parts of Istanbul. Abdülhamid II is considered as the richest Sultan in the Ottoman dynasty in terms of personal money and property. There are still claims of recompensation by his descendants from the Turkish Republic from time to time.

Source: “Maslak Royal Lodges”, p.13, Publication of National Palaces.

Source: www.ogunhaber.com (10/02/2019)

By the time Abdülhamid II became heir apparent, in 1876, after the deposition and tragic massacre of his uncle Sultan Abdülaziz and the dethronement of his two years elder brother Sultan Murad V who went mad in a few months, he had become a very distrustful person, suspecting everyone and everything to the extent of being paranoid. This became the basic characteristic of his 33 years long reign, making him one of the most oppressive Ottoman Sultans. Although he initially assumed a very democratic demeanour when the throne was offered to him and proclaimed a constitutional government, he shut down the parliament almost a year later. Conspiracies to enthrone his mad brother again, the Turco-Russian War in 1877-1878, general strikes, uprisings of minorities, loss of land to foreign powers became excuses for his autocratic rule with an iron fist. He set up his own network of informants and spies who became the nightmare of the Ottoman intelligentsia. However, since no one (least of all a ruler or a leader) can be black or white, Sultan Abdülhamid II was also the founder of some institutions and practices that have survived to this day. Most importantly, he was adamant about improving the education level in the empire. He not only opened primary, secondary and high schools all over the country, but initiated higher education in engineering, art, medicine, veterinary medicine, pharmacy, political science, forestry, in addition to the improvements in military education. The number of minority schools in Istanbul during his reign amounted to 66 Greek, 45 Armenian, 9 Catholic, 34 Jewish, 3 Bulgarian and 11 Protestant schools. The railways that were built during Sultan Abdülhamid II’s time were remarkable in enabling accessibility to the remote corners of the empire. The Berlin-Baghdad, the İzmir-Aydın, trans-Balkans and the Damascus- Mecca- Medina railway lines were constructed with his initiation. However, only the Damascus- Mecca- Medina line was financed with domestic resources. The other lines were outsourced, with serious concessions, to foreign companies and governments.

Source: www.millisaraylar.gov.tr

The Ottoman Empire was already in serious debt when Sultan Abdülhamid II took over. A moratorium had been declared in 1875 during Sultan Abdülaziz’s time. The state was in heavy debt primarily due to the Crimean War (1853-1856) and the investments since the beginning of the 19th century to modernise the country. According to some, lavish expenditure on new palaces were the cause of the financial crises. However, considering the relative modesty of Ottoman palaces with respect to the palaces of other European sovereigns of the time, serious historians disregard this claim as a sole reason. In 1881, the Public Debt Administration (Düyûn-ı Umûmiye) was established to keep account of the foreign debts and the repayments.

Although Sultan Abdülhamid II ruled the country single-handedly for more than three decades, the last years of his reign were full of uprisings, protests, strikes, sabotages and assassinations. The increasing chaos eventually led him to reopen the parliament in 1908. He was dethroned by the parliament a year later when suspected of supporting a big religious and anti-progressive uprising. He was initially exiled to Selanik (Thessaloniki), where he lived until the Ottomans lost the city in 1912. When transferred back to Istanbul, he lived at the Beylerbeyi Palace until his death in 1918.

with his family

Prince Abdülhamid Efendi

If the residences Sultan Abdülhamid II lived in throughout his life were to symbolise the different phases in his life, The Maslak Lodges would correspond to his youth and his initiation as a ruler while the Beylerbeyi Palace stood for his downfall and old age. By coincidence, they were both built at the time of his uncle, Sultan Abdülaziz who shared the same fate of dethronement as his nephews did but who was in addition killed as well. It was at the Imperial Pavilion of the Maslak Royal Lodges where as a prince (şehzade) Abdülhamid Efendi (the title used for princes) was informed that he would be crowned. During his rule, he preferred the Yıldız Palace as an abode instead of the Dolmabahçe Palace which he thought to be lacking in terms of security. Another factor could have been the lingering memory of the deposition of the two previous Sultans at Dolmabahçe. However, his choice of palace did not alter his similar fate.

The Imperial Pavilion (Kasr-ı Hümâyun) is the biggest of the three main buildings at the Maslak Royal Lodges. The building served as the private apartments of the estate. The elegant wooden structure has features from both the European and Ottoman architecture of the time. Inside, the building is structured according to the Ottoman style with all rooms opening onto a landing (called sofa in Turkish) . The beautiful staircase leading to the upper floor was the work of Abdülhamid II himself who was a skilled carpenter and cabinetmaker. It was made by him at his workshop in the Topkapı Palace and said to have been installed here by himself. The baroque style staircase was made without using any nails. Abdülhamid II never gave up his hobby and has left behind various beautiful pieces of furniture that are today exhibited in various palaces and museums in Istanbul.

of the Mâbeyn-i Hümâyûn. Both photos were taken from the adjoining conservatory.

The walls and ceilings inside the building are abundantly decorated with still-life compositions and depictions of garden, countryside and mountain scenes, fit for a country residence. The only bedroom on the ground floor belonged to the prince who was not only afraid of conspiracies but of earthquakes as well. The possibility of jumping out of the window in case of emergency must have seemed reassuring for him.

The second pavilion in the complex is the Mâbeyn-i Hümâyûn which was reserved for the state apartments. This was where the prince worked, received his official visitors and conducted his official duties and affairs. Unfortunately, this building is currently closed to visits. It is stated in the brochure that there are two small rooms on either side of the entrance which could be waiting rooms. The building is connected to the adjoining conservatory by the broad French windows of the large reception room at the back.

The conservatory reveals Abdülhamid’s great interest in flowers and trees. Inside, there are still rare species of trees such as the camellia trees brought from France and cycas trees. There is also a grotto. All the trees, flowers and vegetable gardens of the estate were tended by horticulturalists and arboriculture experts who were hired from Europe. Pools and lakes were another feature of the land. The young prince was very fond of hunting as well. He continued to pursue these hobbies at the Yıldız Palace and its surrounding estate when he moved there as a sultan. In a way, he created a similar atmosphere on a bigger scale there.

This part of the complex was reserved for the aides-de-camp of the young prince. There is also a Turkish bath and a cistern in this section.

The last of the three pavilions, Çadır Köşkü, is a small octagonal building that overlooks the forest. As the name implies (çadır means tent in Turkish), this small building is for daily recreation and repose. The balcony that encircles the entire upper floor is an elegant architectural touch to the building. Today, the ground floor of the building is used as the kitchen of the café that is in operation here. Tables are scattered further down, towards the pond. Sitting under the more than a century old trees for a drink or a light lunch, away from the hubbub of the city, is a very soothing experience.

After your visit, you can extend your excursion to this part of the city with several other activities. For a glimpse of the contemporary life in Istanbul, you can take a bus or a taxi to the state-of-the-art shopping mall İstinye Park where you will find domestic and international luxury brands together with a wide range of culinary choices. Another option would be to go for a stroll along the Bosphorus and end the day at a fish restaurant by the shore.

Thank you for sharing this well researched and informative piece of writing. This is another site to add to my list of places to visit in Istanbul once the weather improves.

Dear Lisa, thank you for reading my post. I am sure you will enjoy visiting the place. Especially in fine weather. Stay safe.