“Whoever rules the waves rules the world” wrote the American naval officer, historian and strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) in his book The Influence of Sea Power Upon History. As an empire that for centuries ruled over lands on three continents, it can be stated that the fate of the Ottoman Empire was also closely related with its success in the seas. The rise and fall of the Ottomans are in parallel with the success and the failure of the Ottoman Navy over time. While a powerful navy force enabled glorious victories on land and sea, its loss of superiority played a major role in the decline of the empire. In that respect, the Naval Museum in Istanbul offers a different perspective to the history of the Ottomans.

The Naval Museum in the Beşiktaş district of Istanbul is a very pleasant museum to visit and it is full of historical surprises. It was founded in 1897 by Lieutenant Commander Süleyman Nutki, in a small building on the premises of the Imperial Dockyard (Tersane-i Amire). The initial name was “The Museum and Library Administration Office”. The objects of the museum were transferred to several places in Anatolia for security reasons when World War II broke out. After the war, the collection was moved to the Dolmabahçe Mosque in Istanbul. Finally, in 1961, the objects were moved to their present location in Beşiktaş. Interestingly, the museum is situated where there once was the private Nuri Demirağ Aircraft Factory and its office buildings. The fact that the place is today situated on one of the busiest avenues in Istanbul makes it difficult to believe but, in 1936 the first private airplanes in Turkey were built here. An extension building construction and renovation took place between 2005-2008. The museum was reopened in 2013.

When you plan a visit to the Naval Museum, I would recommend you to also sightsee another place that is almost next to the museum. This is the mausoleum of the great Ottoman admiral Barbaros Hayrettin Pasha (1478-1546). Born in the Greek island Lesbos, Hızır (his birth name) and his elder brother Oruç were corsairs who raided countries around the Mediterranean. In 1516 the two brothers captured Algiers from the Spanish and Oruç declared himself Sultan. When the Spanish killed his brother in 1518, Hızır acquired his brothers nickname Barbarossa which means red beard in Italian. He then offered homage and entered the service of the Ottoman Sultan, Süleyman the Magnificent. The name Hayrettin (meaning best of faith) was given to him by the Sultan. In 1533 he became the Grand Admiral (Kapudan Pasha) of the Ottoman navy. He conquered Tunisia in 1534. He led military campaigns throughout the Mediterranean Sea and specifically to Majorca, Puglia, Corfu and Venice. The greatest example of his maritime knowledge and ingenuity was the victory of the Ottomans at the battle of Preveza in 1538 when the Crusader Fleet led by Andrea Doria was fatally defeated. In 1543, he was sent by Süleyman the Magnificent with a fleet to fight with the French against Spain. It was then that the Ottoman fleet anchored at the harbour of Nice in France. He retired in 1545 and died in Istanbul the following year.

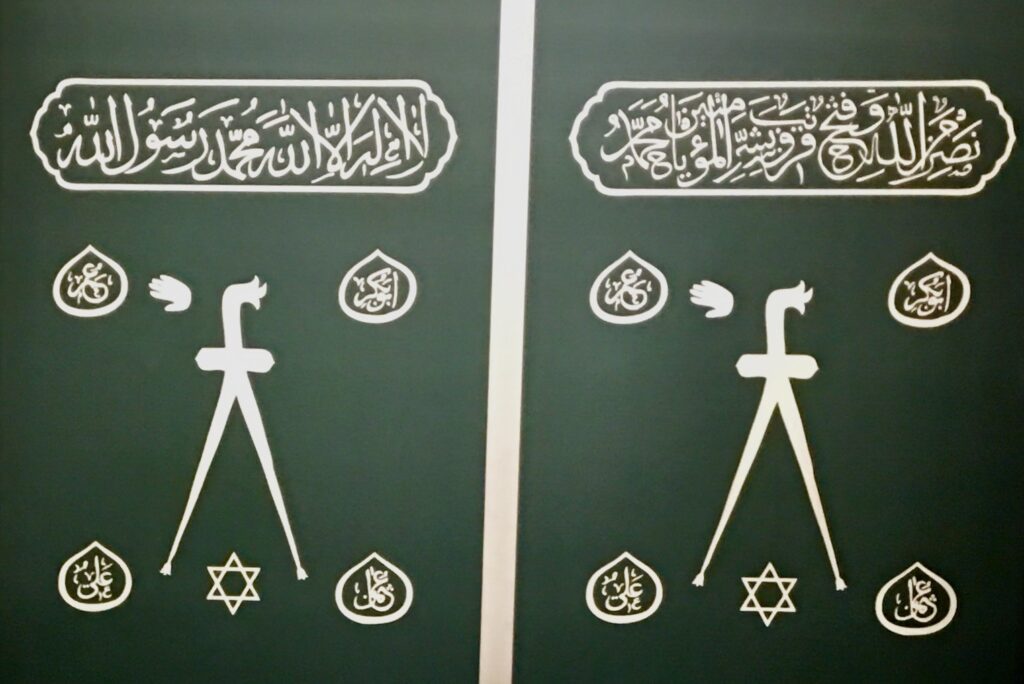

The mausoleum of Barbaros Hayrettin Pasha was built between 1541-1542, before the great admiral died. The architect of the building is the renowned Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan who also built the grand mosque Süleymaniye in the name of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent. The structure is an example of 16th century classical Ottoman architecture. Inside, there are the cists of Barbaros Hayrettin Pasha, his wife and two other Pashas. The cist of Barbaros is covered with the copy of his special ensign. The original one is displayed in the naval museum. Outside, in the garden, there are the tombs of Barbaros’s relatives and acquaintances.

Coming from Central Asia, Turks originally were not a seafaring nation. They became so only after they reached the Aegean and the Mediterranean coasts when they settled in Asia Minor. Although today it is known that Turkish tribes inhabited the lands of the Byzantine Empire in Anatolia long before, historically the official entry of Turks to Asia Minor is accepted as 1071. This was when Sultan Alp Arslan (1029-1072) of the Turkish Seljuk Empire defeated the Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV. Diogenes in the Battle of Manzikert (Malazgirt) on August 26th, 1071. It was a turning point not just for Turks but also for Byzantines. The empire survived four more centuries (albeit an interval of 57 years of reign by the Latin Crusaders in Constantinople) but from then on, there was a never-ending loss of Byzantine lands to Turks. So much so that, by 1453 the capital city Constantinople was practically isolated in the middle of Turkish lands in Europe and Asia Minor.

The first Turkish naval figure that is known in history is the Seljuk Turk, Çaka Bey (pronounced Chaka) who was a soldier in the Seljuk army. He was captured by Byzantine forces during a raid in 1078. He became acquainted with the sea and sailing while he was a captive. He found the opportunity to escape in 1081 when there was a turmoil and change of dynasties in Constantinople. In time, he was able to conquer Izmir (Smyrna) where he built a shipyard. The first fleet, consisting of 50 sailing and row boats, that was built here is considered as the foundation of the Turkish Navy in history. Çaka bey used Izmir as his base for his attacks and raids on Byzantine lands, including the islands of Lesbos, Rhodes, Chios and Samos.

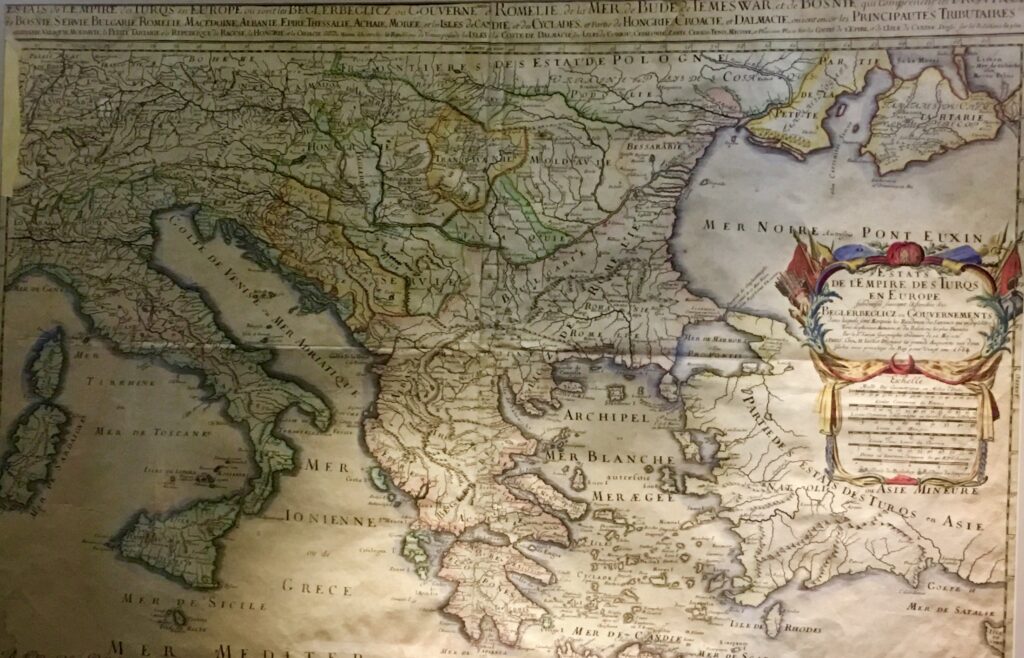

Coloured lithography on paper.

Maritime endeavours of the Turks in Anatolia continued after the fall of the Seljuk Empire (in 1308) which was mainly due to Mongol invasions. Some Turkish city states were already established during the last decade of the empire as it weakened over time. The frontier city states in Western Anatolia, such as the Aydın state (1300-1403) were significantly successful against the Byzantine and Genoese naval forces. For example, Umur Bey, a naval commander from Aydın, seized control of the area from Rhodes to the Dardanelles Strait. In time, the Ottomans, who were also initially a small city state, gained power over the other states. They were conquered one by one until Sultan Mehmet II (a.k.a. the Conqueror) annexed them all to his empire. There is no doubt that, the Ottomans benefited tremendously from the maritime experiences, harbours, facilities and shipyards of the Turkish city states.

Being initially an inland city state, the Ottomans became acquainted with navigation only after they reached the seashores. When they captured Prainetos (Karamürsel) in the Gulf of Izmit in 1324 (according to some sources in 1326), they built the first Ottoman dockyard there, no doubt by benefiting from the experience and knowledge of the former city state Karasi in the area. Karamürsel Alp became the first Ottoman Naval Commander and the fleet that was built there became the nucleus of the future Ottoman Navy.

This galley is stated as the oldest original galley in the world. It was most probably used for excursions by the Sultan because there are neither cannons nor places for warriors on the galley. The Byzantine symbols on the bow and stern of the galley caused claims that she was captured from the Byzantine Empire by Sultan Mehmet II. However, the construction technique of the galley that belonged to a later period disproved this argument.

The first fully equipped Ottoman dockyard was constructed in Gallipoli (Gelibolu) by Saruca Pasha in 1390, during the reign of Sultan Bayezid I (1389-1403). Saruca Pasha was promoted as the first Admiral-in-chief of the Ottomans. A small dockyard was established in the Golden Horn after the conquest of Constantinople (1453). The facilities were improved during the reigns of Sultan Bayezid II (1481-1512), Sultan Selim I (1512-1520) and Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (1520-1566). Not only shipbuilding yards but stores, cannon and powder foundries, sail and rope factories were also established in the vicinity. (The last three shipyards in the Golden Horn were shut down for good in 2013).

Due to the indifference of the succeeding Sultans, in time the Ottoman shipbuilding industry fell behind the technological developments that were achieved by other countries. Apart from tragic defeats, this also caused a major disadvantage for the Ottomans in terms of sailing to the newly discovered continents from where the European countries accumulated the basic capital that would pave the way for their future industrialisation and prosperity. It is true that, Ottoman ships sailed in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, going as far as Sumatra and even briefly capturing Lanzarote, one of the Canary Islands in the 16th century. They were even seen off the eastern coasts of North America, particularly along the shores of the British colonies such as Newfoundland and Virginia. However, these expeditions lacked the required backup to set up a stronghold in those faraway lands.

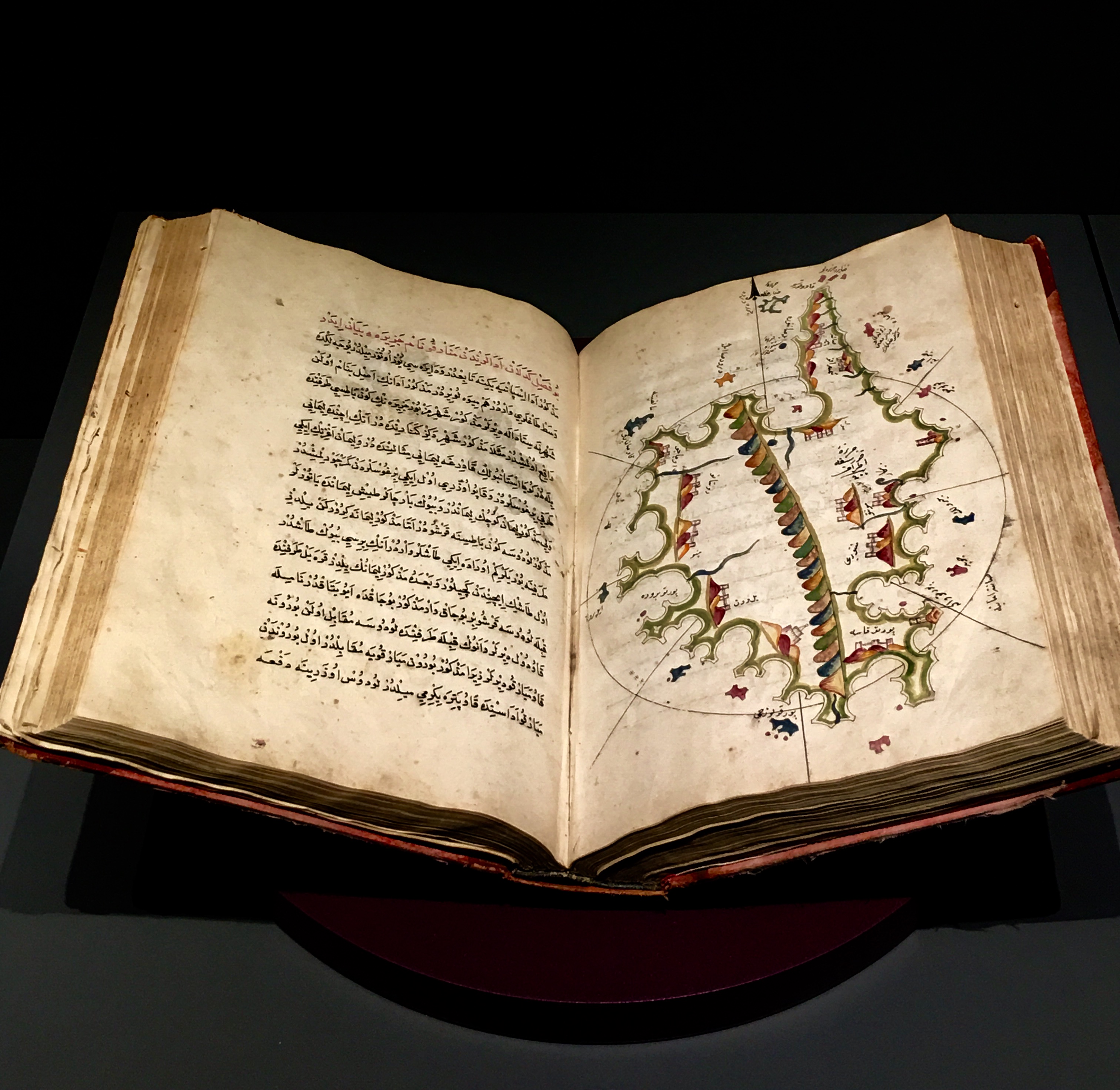

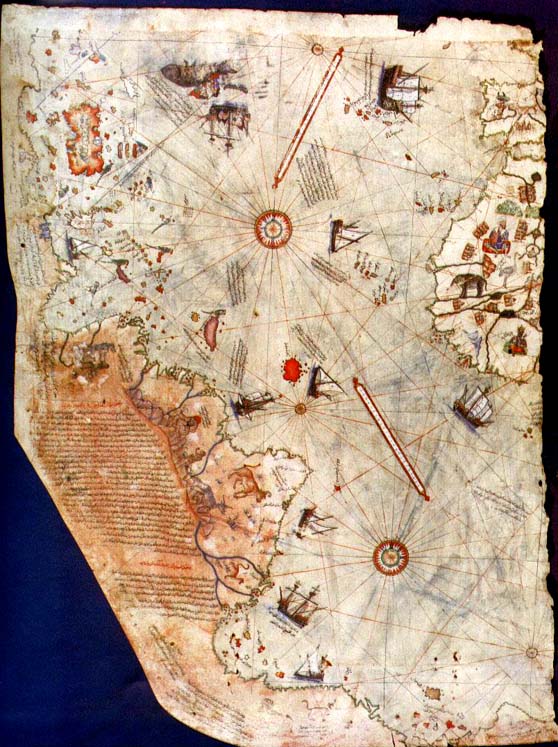

Cartography was a major area of interest for the Ottomans. They used both Islamic and Western sources to draw naval maps. Piri Reis ( -1553), a renowned Ottoman admiral, geographer and cartographer, drew his first map of the world in 1513 using twenty other sources including one of Christopher Columbus’s maps. It was found in the archives of the Topkapı Palace in 1929. It is one of the oldest maps that depicts Australia. The map also shows the Western coasts of Europe and Africa in addition to the East coasts of South America. In 1528, Piri drew a second world map of which only a small part survived to this day. His book, Kitab-ı Bahriye (Book of Navigation), was first published in 1521. Later a revised edition, containing 290 maps, was presented to Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent.

Currently, part of the collection of the Topkapı Palace

Katib Çelebi (1609-1657) was another geographer of the Ottoman period. His book Cihannuma included maps and information about Europe and the New World. The book is regarded as a transition by the Ottomans from the use of Arab and Islamic sources in general (which were considered by the author as deficient in certain aspects) to Western naval sources.

Perhaps the most significant defeat that the Ottoman Navy ever lived through was the one in the naval war of Lepanto (İnebahtı in Turkish). This was the battle on October 7th, 1571 between the Ottomans and the Holy League which was a coalition of Catholic States under the leadership of Pope Pius V. The main forces of the coalition were Spain and Venice. The battle that took place off the southwestern coast of Greece was part of the power struggle between the Ottomans and Venetians in the Mediterranean after the conquest of Cyprus by the Ottomans on August 6th, 1571. Lepanto was the first major victory of a Christian naval force over the Turks. Turks lost the majority of their ships and the most remarkable commanders of the Ottoman Navy.

The battle is noteworthy in several other aspects as well. For example, Lepanto is considered as the climax of the age of galley warfare in the Mediterranean. Galleys which were vessels that were propelled mainly by rowing, had been in use in the Mediterranean since ancient times. Lepanto is considered to be the climax of the age of galleys. After that, galleys were replaced by other, technologically more advanced vessels. Another interesting fact is that, the famous Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes also fought in this battle against the Turks. He was wounded in the chest in two places and his left arm was maimed forever. He was to be captured by Ottoman corsairs in 1575 and taken to Algeria. Some sources claim that he was later brought to Istanbul as a slave and made to work at the construction of the Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque. Kılıç Ali Pasha was a commander in the Ottoman naval forces who successfully defended the left flank of the navy at Lepanto without losing any of the ships under his command.

On October 17th, 1848, during the Ottoman reform period, Sultan Abdülmecit attended the examinations in the navy, thereby setting a tradition. This throne was used by the Sultans when the examinations where held on the island of Heybeliada.

Even though the Ottoman Navy was late by at least half a century in first converting its ships into sailing vessels (galleons) and later to steam boats, there were also efforts by some Sultans to modernise the Navy. The French aristocrat and engineer, Baron Francois de Tott (1733-1795) was employed to that effect. He was involved in the reformation of the Ottoman army and navy. His teachings of naval science to the Ottomans later led to the establishment of the Navy Engineering School (later to become the Naval Academy) in1773 by Algerian Ghazi Hasan Pasha. Modernisation attempts continued with the reformist Sultans of the 19th century. After the abolishment of the Janissaries in 1826 by Sultan Mahmut II, the education system and the uniforms of the whole army, as well as the navy were renewed. Large numbers of officers were sent abroad for education and training. A Naval High School was established in 1852 on Heybeliada, one of the Princes’ Islands in Istanbul.

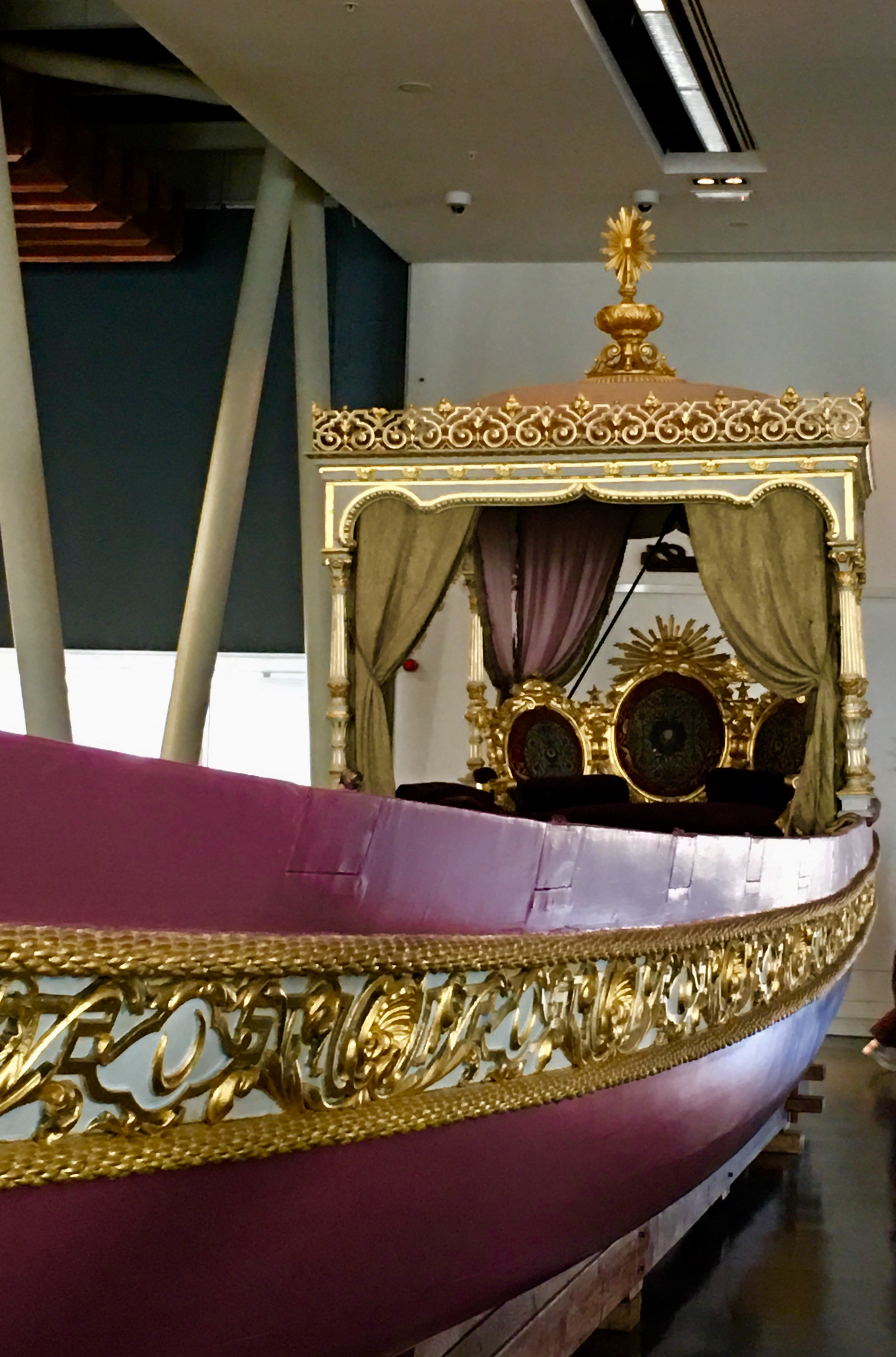

The items of the museum that are imprinted in one’s memory are no doubt the beautiful and elegant imperial caiques. 15 out of the 33 boats and caiques in the collection of the museum are imperial caiques, meaning that they could only be used by the imperial family. These were the most grandiose ones with lengths that varied between 15 to 32 metres. They were made to impose the magnificence and the opulence of the empire. The Sultan’s caique could only be used by him, his mother, his wives and his children. The Grand Viziers of the empire also had their own caiques that were naturally less lavishly adorned. The decorations on the caiques reflected the taste of the era they were built in. The ones in the collection of the Naval Museum are all from the 19th century.

Apart from being a means of daily transport, the imperial caiques were used by the Sultans for the coronation and sword girding ceremonies, Ramadan celebrations, Friday prayer service parades and sightseeing excursions. The imperial caiques had seven pairs of oars while those of the accompanying caiques had five pairs. These last ones would be carrying all the required equipment such as coffee sets, food and clothing that would be needed by the Sultan during his trip.

The number of the pairs of oars of the caiques was not a light matter. The caiques of the other dignitaries of the state and those of the foreign diplomats had to abide by the rules for this and the decorations on their vessels. For example, to honour the British, Sultan Selim III gave special permission to the British Ambassador in Istanbul to have a caique with seven pairs of oars after the British Admiral Nelson burned and destroyed the French fleet on August 1st, 1798 in Aboukir, Egypt. Likewise, the American Ambassador Samuel Cox, who lived in Istanbul between 1885-1887, was granted special permission by Sultan Abdülhamit II to have a wooden American eagle mounted on his caique as a figurehead.

When the Sultan set sail with his caique, a gun salute was given from all the ships anchored in the harbour, from the Maiden Tower and various points by the shore. This would be a long procession with some caiques making way for the Sultan and others following him. The people of Istanbul would rush to the shore when they heard the gun shots in order to see him go by.

A diplomatic scandal occurred in 1860 when Marquis de la Valette, the French Ambassador in Istanbul, decided to add two more pairs of oars to his caique. One day as he was gliding over the Bosphorus, Istanbulites thought the Sultan was passing and they applauded. The Ottoman Palace and Sultan Abdülmecit put up with this indecency because of the delicate economic relations with France at the time. However, they retaliated in a different manner. The Ottoman Ambassador in Paris, Ahmet Vefik Pasha, had his black carriage painted in white. When he went about Paris in his white carriage, thinking that Napoleon III was passing by, Parisians cheered and saluted him because only the carriages that belonged to the French Palace were allowed to be in white. The Ottoman Ambassador was immediately informed by the French court that no such thing would be allowed. Ahmet Vefik Pasha’s response was, “I will stop using the white carriage as soon as you stop using the caique with the seven pairs of oars”.

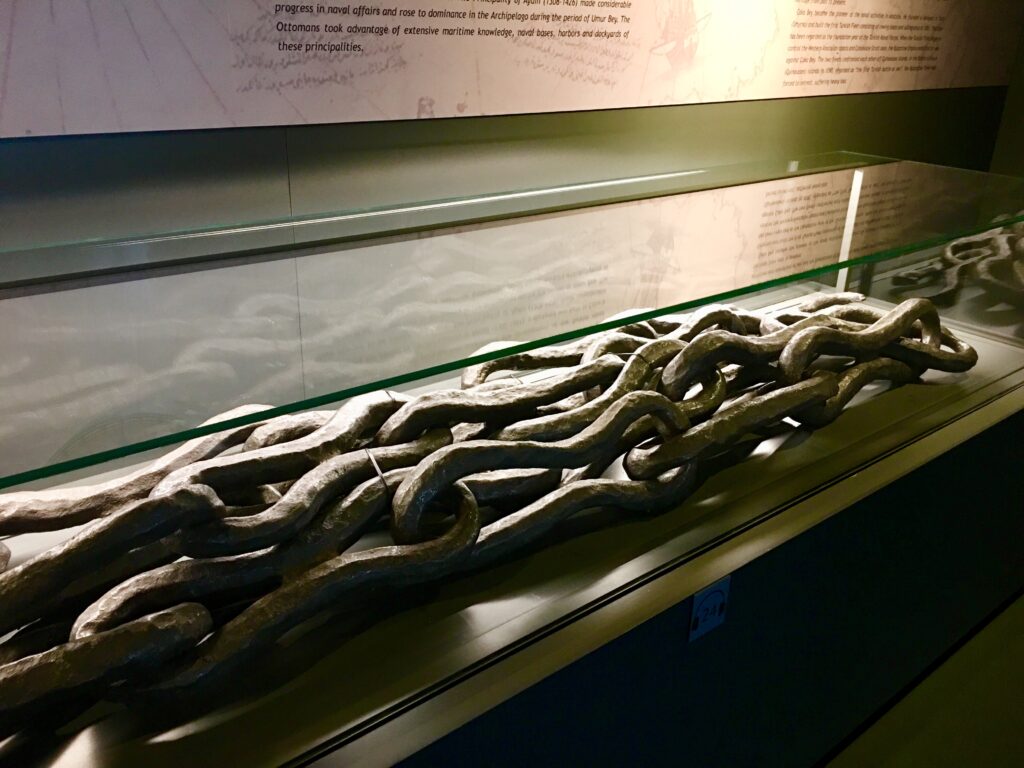

One of the interesting items in the museum’s possession is part of the chain that was stretched by the Byzantines in 1453 across the mouth of the Golden Horn in order to prevent the entry of Ottoman ships. Having completed the preparations, Sultan Mehmet II set off with his army from Edirne (the capital of the Ottomans at the time in Thrace) for the siege of Constantinople on March 23rd, 1453. Upon receiving this news, a chain was stretched across the Golden Horn by the order of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos on April 2nd, 1453. The chain that was fastened to the Tower of Centenarion and the Galata Walls on the opposite shore was the making of the Venetian engineer Bartolomeo Soligo. It was 550 metres long, weighed 4,5 tonnes and consisted of 407 links. As it is known, this precaution did not stop the Turks who, with the ingenuity of the young Sultan, pushed their ships on land, up the hill of Galata and landed them inside the Golden Horn. The chain that is on display is only part of the famous chain. This 33 metres long chain weighs 963 kilograms and has 69 links.

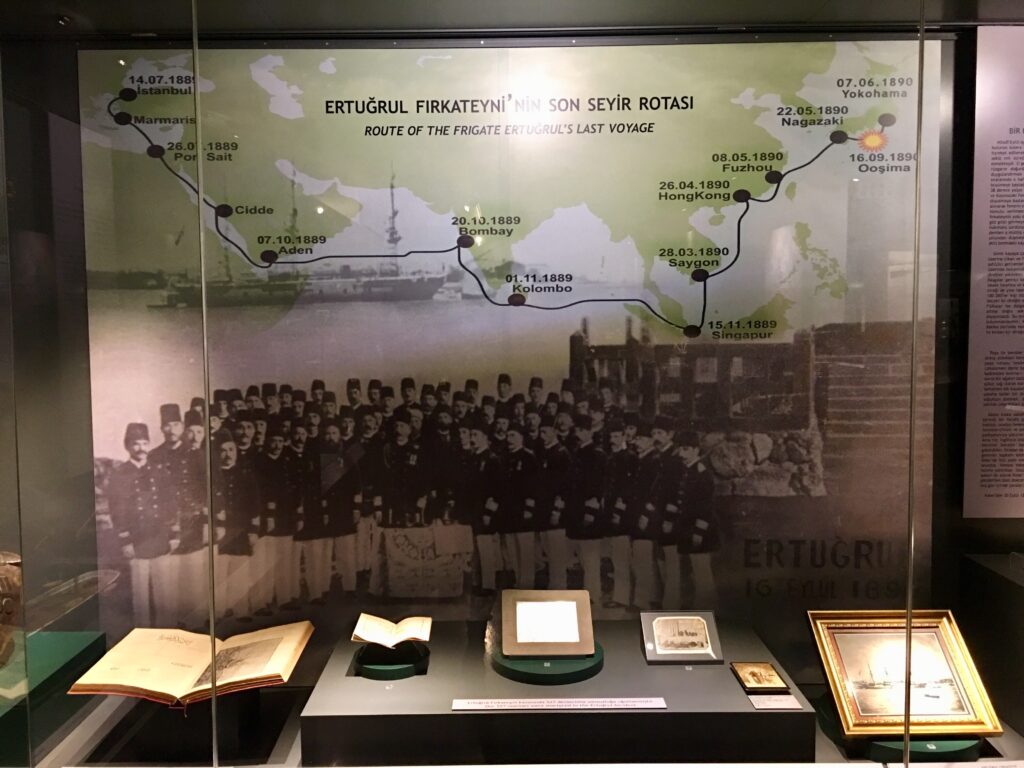

The Ertuğrul Incident is a tragic event in the Turkish naval history that is also commemorated in the Naval Museum. It is the story of sailors who were on a peace mission in faraway lands but unfortunately most of them could never return home. After the visit of the Japanese Prince Komatsu in 1881, Sultan Abdülhamit II decided to send the Ertuğrul Frigate in 1889 as an indication of goodwill. The frigate set sail from Istanbul on July 14th, 1889 with a total number of 612 officers and cadets. Two accidents occurred while passing through the Suez Canal but the voyage continued. The frigate reached Nagasaki on May 22nd, 1890 and Yokohama on June 7th, 1890. The commander, Osman Pasha, presented the gifts and the medal sent by the Sultan to the Emperor of Japan. Having completed the diplomatic mission, the Ertuğrul Frigate set sail home. However, on September 16th, 1890 the ship hit the reefs and sank off the Oshima Island.

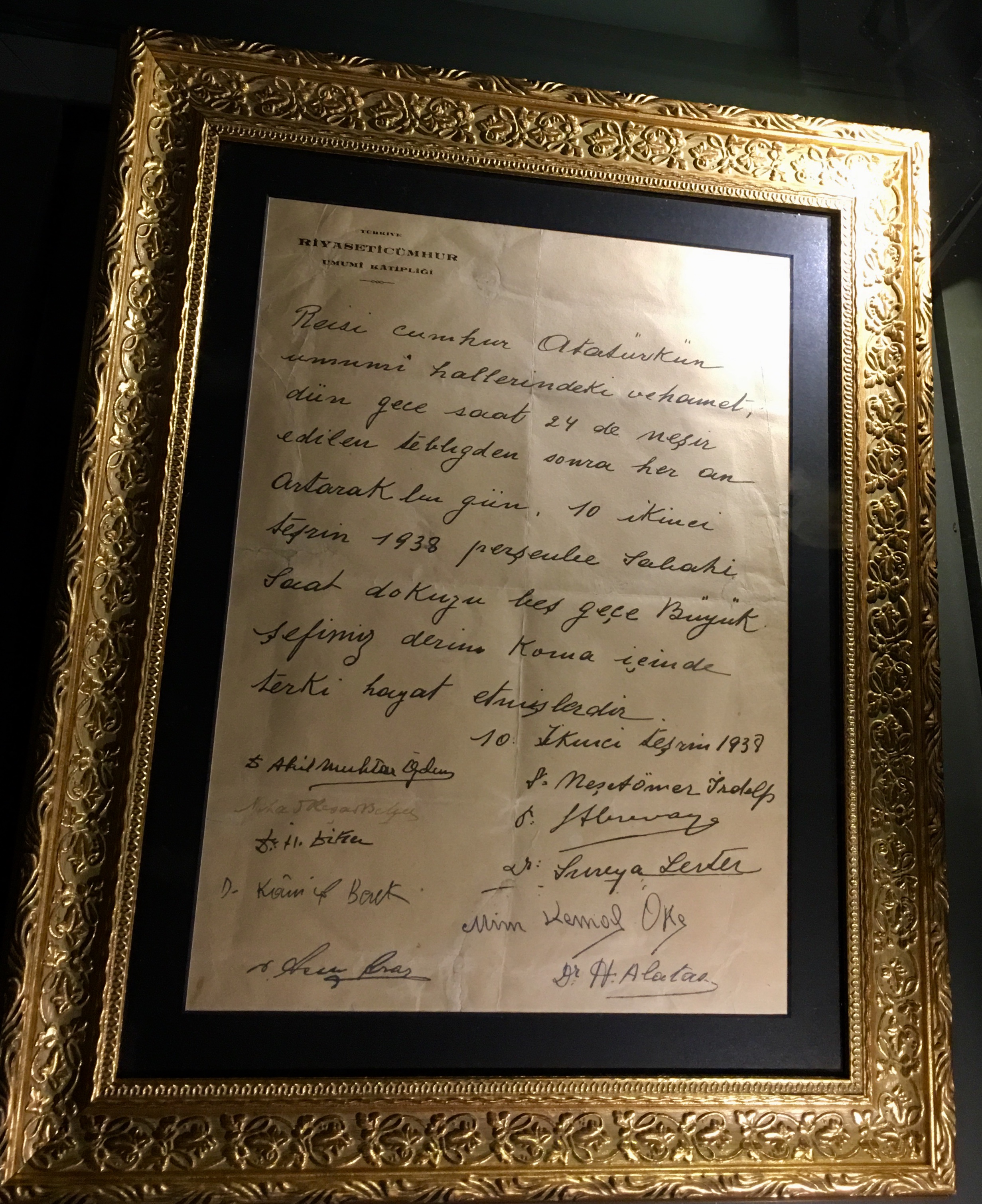

The museum’s collection also has items related with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic. The first one that is encountered is his small boat with one pair of oars, with his initials, MKA, inscribed on each of them. This boat made of mahogany was used by Atatürk when he stayed at the Florya Presidential Palace in Istanbul. Perhaps the most unexpected item at the museum is Atatürk’s death certificate that was signed by his attending doctors when he died at the Dolmabahçe Palace on November 10th, 1938.

Like any other museum, the Naval Museum has many other interesting items in its collection for eyes that can see and minds that can reflect. I personally have visited it on a very cold, rainy day and have enjoyed it very much. I hope you will too.

To share this post

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

About the author