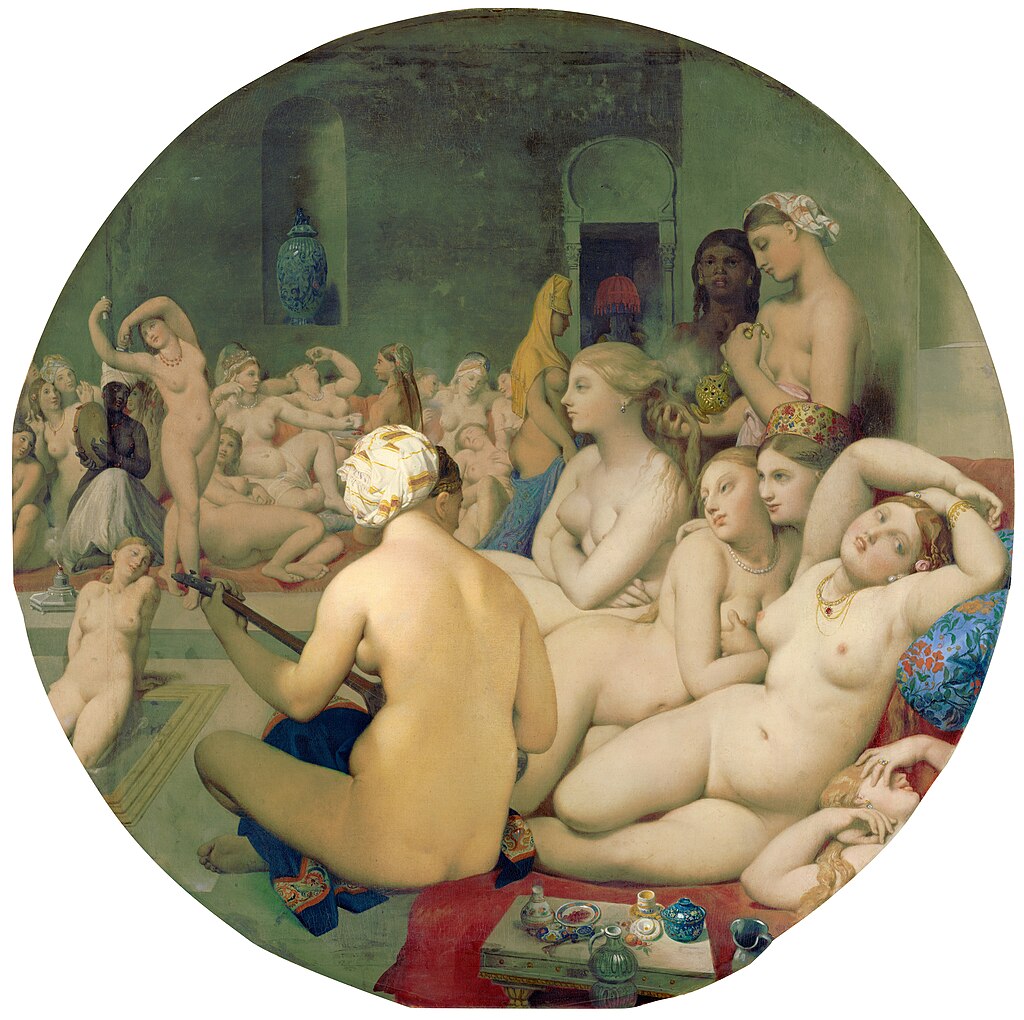

The Turkish Bath has no doubt historically been one of the most erotically evocative traditions of the Ottomans for the Western mind. Similar to the Harem, Turkish Baths have been a subject of curiosity and often of misleading information for foreigners. Artists such as Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), who could never have set foot inside the women’s section of a Turkish Bath, have certainly been the main contributors to this imaginary ambience with their paintings. As it was mentioned in a previous post on this site about the Harem, Turkish Baths were in no way an environment where free and unrestricted nudity prevailed. Both the men’s and women’s sections had rules concerning attire and behaviour on the premises. On the other hand, there have also been more realistic portrayals based on the accounts of eye-witnesses. As for the case of Ingres, who is said to have been inspired by the memoirs of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762), he seems to have given in to the temptation of his imagination, for a good cause as an artist. Namely, that of creating art.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)

Louvre Museum

Different forms of baths have existed in Anatolia for thousands of years. Gymnasiums with adjoining baths for athletes in ancient Greek sites and the more developed Roman or Byzantine baths are frequently encountered as a part of the rich archaeological heritage of the Asia Minor. Excavations of even more ancient sites that belong to the Hittite Empire (1650-1200 B.C.) or the Phrygians (1200-700 B.C.) have also revealed structures that served the same purpose. On the other hand, Turks already had a tradition of bodily cleaning and washing before they came to Anatolia. In Central Asia where Turks were nomads by nature, they had special tents reserved for bathing. During their centuries long westward exodus they evidently adapted to the architectural structures that existed for this purpose in the lands they crossed or stayed for some time. The Seljuk Turks have most probably been inspired by the baths that they encountered in Iran when they settled down, first in Iran and later in Anatolia while the usage of bathing tents continued during military campaigns.

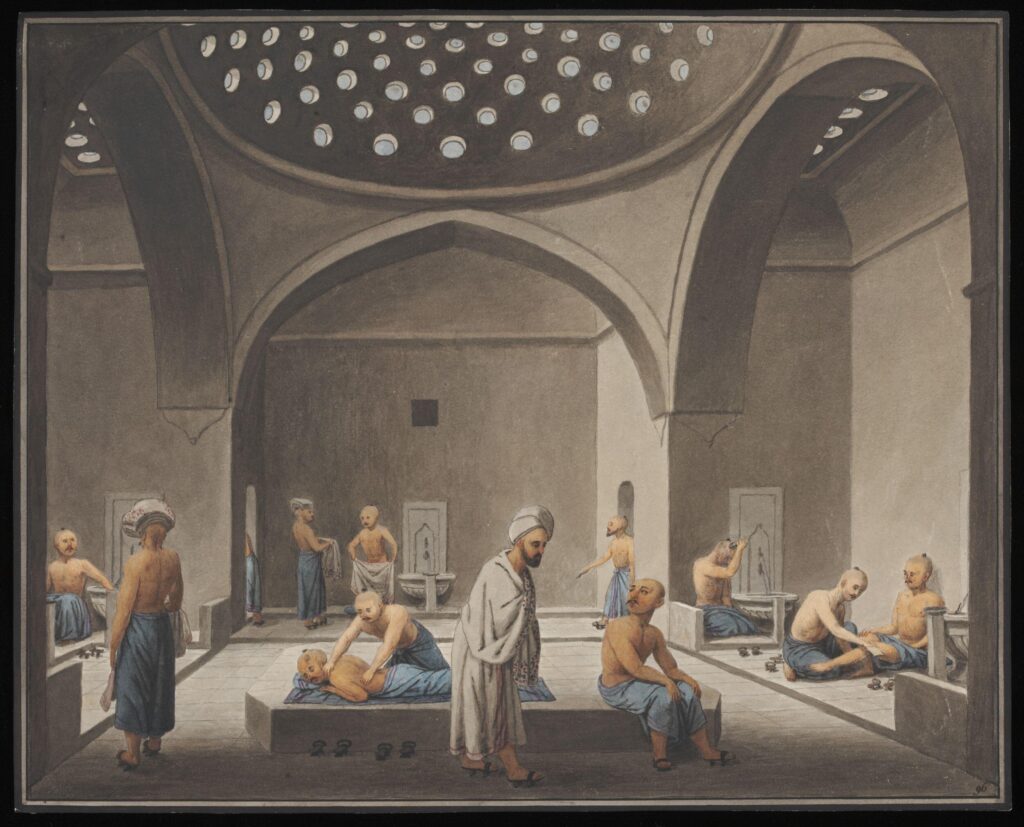

Jean- Jacques- Francois Le Barbier (1738-1826)

sothebys.com

Today, despite the claims of different cultures and countries, it is a fact that the Turkish Bath or Hamam, as it is locally named, has a unique worldwide reputation. (Hamam is a borrowed word from Arabic related to heating or keeping warm). The Turkish Bath in its present structure was created in the XV. century by the Ottomans. They were designed based on Roman and Byzantine baths but some of their features were modified to comply with Islamic beliefs and practices. This seemed nothing but natural as the Ottomans regarded themselves, starting from Sultan Mehmet II the Conqueror (1.r. 1444-1446, 2.r. 1451-1481), as the natural heirs of the Roman Empire. They, just as easily, regarded Roman codes of justice as reference to develop their own laws and decrees to maintain order in the Ottoman realm.

Anonymous Greek Artist

Victoria and Albert Museum

Like the Romans, Ottomans built both public baths and private ones in palaces and mansions. Some public baths, such as those in market places proved to be very lucrative business operations. Others were mainly built as a part of big mosque complexes such as the one you can see today on the premises of the Süleymaniye Mosque. These baths would typically be part of a foundation charter (vakıfname) to provide financial support for the maintenance of the related mosque. Most of the monumental historic Ottoman baths were built during the XVI. century when a wide range of reconstruction on Ottoman lands took place. Mimar Sinan (the renowned architect of Kanuni Sultan Süleyman (r. 1520-1566) – named as Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent by Westerners) alone built 59 Turkish Baths in his life time, 45 of them being in Istanbul or its environs. Turkish Bath constructions decreased over time and were totally restricted by a Sultan’s decree in the 18th century in order to prevent the ample use of water and wood.

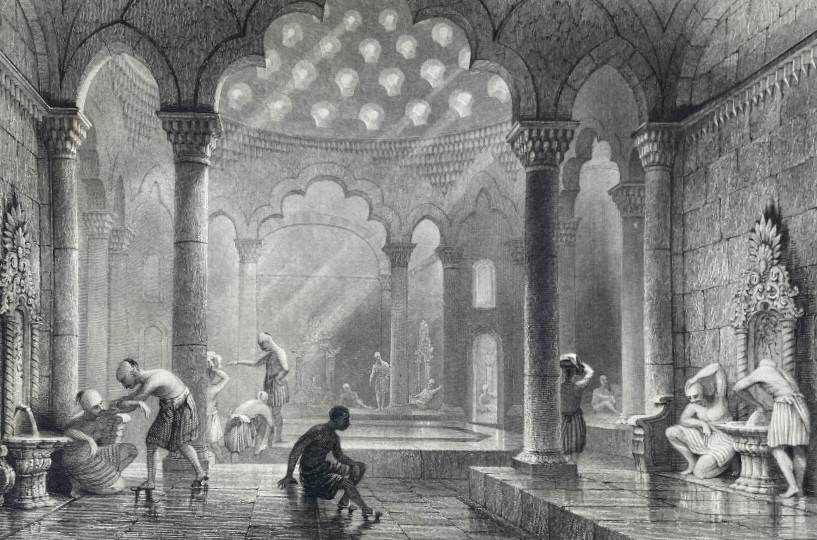

There are many similarities but also some differences between Roman and Turkish Baths. It is known that Romans further developed the Greek baths that existed before their time. The main architectural and structural change was the heating system that was utilised. The breakthrough came from the architect Sergius Orata, who is believed to have lived during the 1st century B.C. Orata was the one who invented the system of central heating in baths where there is a flow of hot air current beneath the floor. This convenient characteristic was readily adopted by the Ottomans in bath constructions and the section where the furnace stood acquired the name külhan instead of the Latin praefurnium. The first section that a patron sets foot in a bath is the camekân or soyunmalık. It corresponds to the apoditerium in Roman baths where clothes are taken off. In a Turkish Bath you are supposed to wrap a peştemal (a special piece of cotton cloth that is used both to cover and later to dry the body) around yourself in order to conceal your private parts. This is also the part of the bath where the walls are lined with divans and cushions. It is customary to lie down and rest here after the whole bathing experience while traditional sherbets, refreshing fruit juices and Turkish coffee is served. There is usually a decorative fountain with running water or a sprinkler in the middle of the hall that provides a soothing and relaxing echo. The next part in Roman baths, named as frigidarium does not exist in Turkish Baths. There used to be big pools of cold water in this section. It must be pointed out that there are controversial views regarding the frigidarium of Roman baths. Some sources claim that the cold-water phase was at the very end of bathing while according to some others, it was at the beginning. There are also others asserting that Romans took a cold swim both before and after the actual washing phase. The confusion might be due to the location of this section which was usually at the centre. Whichever sequence was applied by the Romans, this part was eliminated by Turks as it is against Islamic belief and rituals to bath in still water. Traditionally, the water needs to be running for hygenic concerns. Next comes the ılıklık, called the tepidarium in the Roman version. A tepid warm chamber, usually rectangular in shape, where procedures such as shaving or epilation is performed. Toilets are also in this area. This is also the massage and ointment area in Roman baths. In Turkish Baths that you can go to today, you stay and rest in this chamber for a while, so that your body can get ready for the hottest part, the sıcaklık (caldarium in Roman baths).

Sıcaklık, is the section of a Turkish Bath where the actual bath experience takes place. It is a big hall with an elevated marble structure called göbek taşı (sometimes referred to as central or naval stone in English) in the middle. The naval stone is heated as well as the floor and the walls of this section. Around the central hall, there are small chambers where you can bath on your own or as a family or a group of friends. Upon entering the sıcaklık, you are left to lie down and rest on this naval stone for a while. During this time, the body warms up and the blood circulation is said to accelerate. Sweating helps get rid of toxins and your skin gets ready for the exfoliation that will follow. The purpose of exfoliation is to get rid of the dead skin cells.

You can prefer to wash yourself in a Turkish Bath if you want to but, the real experience is to let professionals do that for you. In the men’s section this person is a male called a tellak while the female counterpart in the women’s section is called a natır. No need to say, traditional Turkish Baths have either separate working hours (sometimes days) or they have different sections for men and women. A bath is called “single” if there is one facility that mainly serves men. Women are hosted during specific hours or days. On the other hand, there are also “double” baths where architecturally there are two separate sections to serve each gender simultaneously. The men’s section tends to be larger and the entrance is generally from a main street or a square while the women’s part is accessed through a door that opens to a side street. This is stated to be due to concerns about privacy.

Engraving by William Greatbach (1802-1885)

Historically, Turkish Baths were not only for bathing and relaxing but, especially for women, they were places to socialise and gather for special celebrations and events such as the birth of a child, an engagement or a wedding. Celebrations would be accompanied by music and entertainment. Bridal Hamam events, where a whole day is spent at the bath before the wedding, are still popular in the rural parts of the country. (The male version of this event is the Groom’s Hamam in the men’s section). Another widespread tradition was for mothers to look for the best possible candidates that they would deem worthy of their sons as a future bride. The bath would in that case be a perfect environment to detect any unwanted physical defects.

Jean- Etienne Liotard (1702-1789)

Apart from special events, Turkish Baths were also perfect places for women to catch up with the latest gossips and scandals in town, in an atmosphere devoid of the usual religious and social pressure that prevailed for them at the time. An excellent and most interesting western eyewitness in this case is Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who was the wife of the British Ambassador in Istanbul between 1717-1718. Lady Montagu who used to frequent Turkish Bathhouses herself, made the following observations:

“In short, this is the women’s coffee house, where all the news of the town is told, scandal invented etc. They generally take this diversion once a week, and stay there at least four or five hours without getting cold by immediate coming out of the hot-bath into the cool room, which was very surprising to me.” (The Turkish Embassy Letters, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Edited by Teresa Heffernan and Daniel O’Quinn, Broadview Books, London, 2012)

the Kılıç Ali Paşa Turkish Bath on the right in Tophane, Karaköy

Another quotation from Lady Montagu is as follows:

“I went to the bagnio about ten o’clock. It was already full of women. (…) I believe in the whole there were two hundred women, and yet none of those disdainful smiles, or satiric whispers that never fail in our assemblies, when anybody appears that is not dressed exactly in the fashion. They repeated over and over to me, Uzelle, pek uzelle, which is nothing but Charming, very charming. (…) There were many amongst them as exactly proportioned as ever any goddess was drawn by the pencil of Guido or Titian, and most of their skins shiningly white, only adorned by their beautiful hair divided into many tresses hanging on their shoulders, braided either with pearl or ribbon, perfectly representing the figures of the Graces.” (ibid)

The Ottoman tradition of going regularly to a Turkish Bath waned by the second half of the 19th century as blocks of apartments slowly began to replace the one or two-storey conventional houses in big cities. The new abodes had bathrooms of their own and the need to go to district baths diminished. Nevertheless, during the 1960s people still went to Turkish Baths on a monthly basis. The habit continued to subside in the following decades. Today, Turkish Baths have become more of a touristic activity even though there are still some locals who go to a bath once in a while. The term “touristic” should not allude to a pejorative meaning in this case since now, they are more closely inspected for that very reason. In some facilities, the standard of hygiene and cleanliness is really high.

Names of a few baths in Istanbul that you might want to consider are given below:

with the Lokanta 1741 restaurant inside

The Kılıç Ali Paşa Turkish Bath in Tophane, Karaköy (https://www.kilicalipasahamami.com/) can be recommended by the author of this site based on a recent experience. Working hours, rules and price information should be looked into on the web site. It is a clean and professionally run bath. The building itself is historical and it is a part of the Kılıç Ali Paşa Mosque complex nearby. The whole complex was built in 1578-1587 by Mimar Sinan. The bath was completed in 1583. It is a single bath, built for the use of the naval infantry soldiers of the Ottoman Navy. Kılıç Ali Pasha, who was originally an Italian farmer from Calabria in Italy, was an important figure in Ottoman history. He later converted to Islam and in time rose to the rank of Grand Admiral of the Ottoman naval forces. More information about him and the beautiful mosque complex that was built by his order and finance will be the subject of a future post.

Turkish Bath Culture Museum

ample light while preserving privacy

Turkish Bath Culture Museum

Another historical bath that was also built by Mimar Sinan is the Hürrem Sultan Bath (https://www.hurremsultanhamami.com/en/) in the Ayasofya Square. The bath was built in 1556-1557 by the order of the legendary wife of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, Hürrem Sultan (a.k.a. Roxalana). Needless to say, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent also had a bath built within the complex of his magnificent Süleymaniye Mosque. The Süleymaniye Bath, built between 1550-1557, (https://www.suleymaniyehamami.com.tr/) is also in operation.

Turkish Bath. The central stone (göbek taşı)

is normally much wider and higher.

As stated above, hamam construction was prohibited by Sultans in the 18th century due to concerns about wood and water shortages. The last Turkish Bath that was built before this ban was the Cağaloğlu Bath (https://cagalogluhamami.com.tr/) that was mentioned on this site in relation to the fine dining restaurant Lokanta 1741 (now on Michelin 2024 list) that is inside the historical bath building.

Lastly, if you are looking for an unconventional mixed bath where women and men are served in the same bath and at the same time, you might want to look into the Çukurcuma Hamamı 1831 (http://www.cukurcumahamami.com/en). The facility which is within the boundaries of Beyoğlu is a part of the Hamamhane Hotel (https://www.hammamhane.com/en/)

If you are curious about Turkish Baths but feel intimidated by the anticipated experience for one reason or another, you can still have a glimpse of the culture by visiting the Bayezid II Turkish Bath Culture Museum (II. Bayezid Türk Hamam Kültürü Müzesi) in the Old City. The bath is an example of early Ottoman architecture in Istanbul and was part of the Sultan Bayezid II (r. 1481-1512) complex. The close by Bayezid Mosque and its complex was built between 1501-1506 by the order of Bayezid II who was the son of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror. It is also known as Hamam-ı Kebir because it is the largest Turkish Bath in Istanbul. Some people also call it the Patrona Bath because this was where the historically renowned Patrona Halil Rebellion (1730) started. Patrona Halil, who was a former sailor, was working as an attendant (tellak) in this bath. The uprising that he instigated ended the famous Tulip Era (1718-1730). Riots that lasted for days resulted in the dethronement of Sultan Ahmet III (r.1703-1730) and the decapitation of the Grand Vizier Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha.

The museum building was built as a double bath with separate sections for women and men. Inside, you will not only be able to observe the architecture and the traditional sections of a Turkish Bath but will also see the authentic goods that were a part of the Turkish bathing culture. A selection of old sherbet glasses, bath bowls, pumice stones, clay holders, bath towels (peşkir), waist wraps (peştemal), exfoliating gloves (hamam kesesi) and clogs (nalın) will provide you with an insight about this centuries-old custom.

Fantastic article. Beautifully written and meticulously researched. I remember going to hamam with my grandmother in the 50’s and eating lunch there with other ladies. She used to use this opportunity to scan eligible young ladies as potential daughter in laws.

Thank you Ülgen Hanim

Gülçin Cribb

I thank you in return Gülçin Hanım for your comment and your continuing support for my blog since the very beginning. It is very valuable for me. Best wishes…

Gulcin, thanks for sharing this interesting article!