The Galata district of Istanbul has plenty to offer to an inquisitive mind that has a special interest in history. You can literally wonder in the maze of its streets and feel like you are travelling in time. The history and the Genoese background of Galata were covered in my previous post that concentrated more on the area between the Galata Tower and Karaköy. (You can access the post by clicking on the link.) Alternative routes are numerous around Galata. You will soon discover that somehow most of them take you to the Galata Tower. As previously mentioned, going up the Tower is recommended for a good understanding of the layout of the area.

This time, let us take the Tünel on the İstiklal Caddesi (Avenue) as the starting point. Tünel literally means tunnel in Turkish. The name actually comes from the funicular that operates from Karaköy to this point. However, tradionally it is also used to express the section of the İstiklal that is closer to the Golden Horn. As most visitors find out, İstiklal is a long and winding avenue starting from the Taksim Square. Tünel is the final destination of this promenade.

The steps were removed in 1956.

Source: SALT Research, Photography Archive

The Tünel funicular is still a very widely used means of travel up the hill from Karaköy. Prior to the construction of the funicular, commuting between the finance and trade centre of the city Karaköy and the cultural and night-life attraction point Beyoğlu (also known as Pera at the time) was by way of the Yüksek Kaldırım Caddesi (Avenue). This avenue was a staircase street that dated back to the Genoese period of the area. Having a stepwise structure on a steep slope, it was only open to pedestrian traffic. Carrying any kind of load up or down the avenue was obviously a very tedious task. Today, the avenue is still there although the steps have long been destroyed and paved to enable automobile access.

Tünel was built by the French engineer Eugène-Henri Gavan who came to Istanbul on a visit in 1867. Gavan took interest in the pedestrian traffic on the Yüksek Kaldırım Avenue. (The name of the avenue means High Pavement in Turkish.) According to his observations, 40,000 people on average were using this route on a daily basis. This made him think of a project to transport people up the hill. He presented his proposal to the Sultan in 1869. The approved project was started in 1871 and the funicular opened its doors to the public in 1875. Tünel is considered as one of the oldest underground transportation systems in the world. It was built after the Tube in London (1863) but before the Budapest (1896) and Paris (1900) metro systems. However, with a length of 550.80 metres, today it can be considered also as the shortest system in the world.

The square in front of the İstiklal entrance of the Tünel funicular is officially named as the Tünel Square. Turning your back towards the entrance to the station, you will see a block of buildings situated right across the square. The three buildings that form the complex also surround a passageway, known as the Tünel Passage. The passageway was built in 1886 and it is still vibrant with the cafes and restaurants inside. It has two other entrances by means of which the Tünel Square is connected to two side streets (namely, Ensiz and Sofyalı). The land originally belonged to and was part of the cemetery of the Galata Mevlevi Lodge. It was sold to the foreign company that initially operated the Tünel funicular. The upper floors of the three buildings were once luxurious apartments where prominent families of Istanbul used to reside. They were abandoned in time as the cultural texture of the area changed over the centuries. The basement of the complex was allocated to the mechanical operation system of the funicular. At the corner, you can still see the old brick chimney that was used at the time when the funicular was initially operated with steam power. In the beginning of the 1980s, the building was used as the Beyoğlu Justice Hall. Currently, it is owned by a Turkish company.

The municipality was established in 1858 and it was the first municipality in the Ottoman realm. The building was built between 1879-1883 and it is the work of art of the Italian architect Giovanni Battista Barborini. The structure rising behind the municipality is the building of the Tünel funicular. The brick chimney visible on the left is at the corner of the Tünel Passage complex and it was originally part of the funicular system.

Now, walk from the Tünel Square towards the İstiklal Avenue (in the direction of the Taksim Square). Shortly, you will see the Galip Dede Avenue on your right. Turn into this avenue instead of continuing on the İstiklal. The Galip Dede Avenue merges with the Yüksek Kaldırım Avenue on its way down the hill. As mentioned above, this was once a step street that went all the way down to the shore, connecting Karaköy to Beyoğlu. At the time, it was the music centre of the city with shops that sold musical instruments, music books, music sheets and records. There are still a few of them that are trying to resist the tide of change in the music industry and the general spirit of the area. Most of the previous shops have now been replaced by those that sell souvenirs and all kinds of other knick-knacks.

The building on the left-hand-side of the gate is the Mausoleum of Halet Efendi and the one on the right is the Library of Halet Efendi and the muvakkithane.

The building on the right is the Mausoleum of Şeyh Galip Dede (1757-1799)

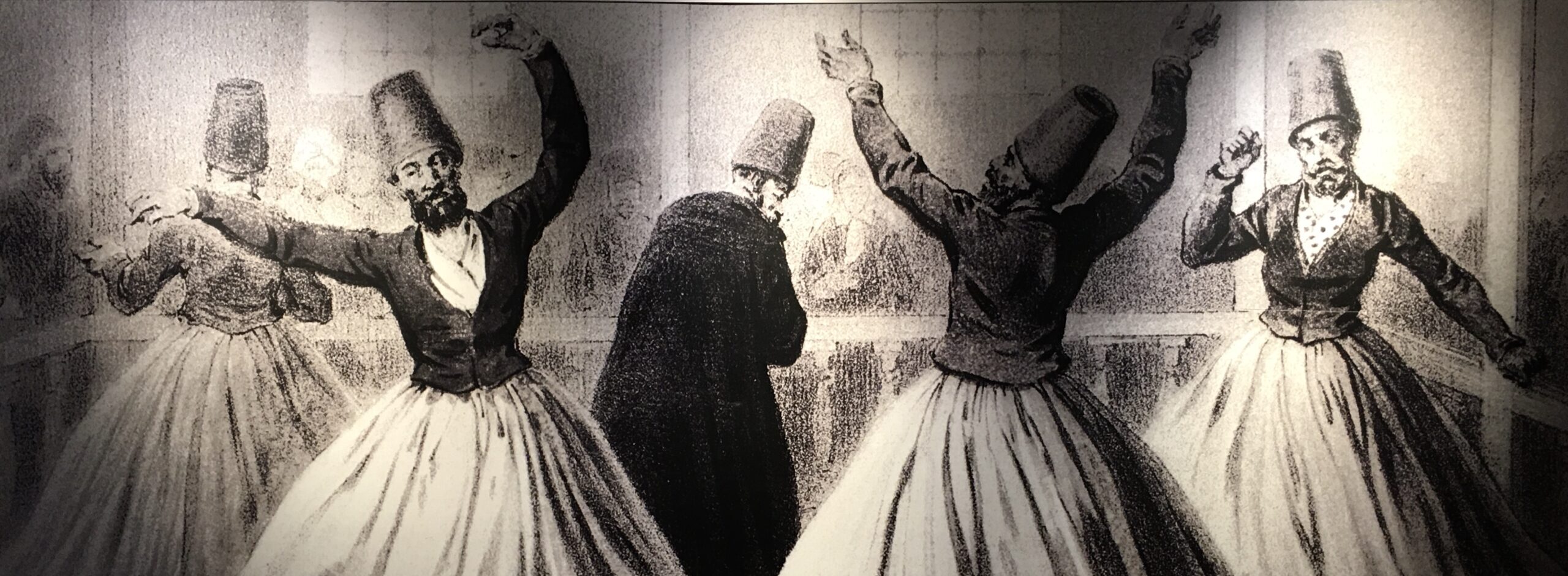

Before long, you will see an Ottoman building complex on your left. Its beautiful main entrance will definitely catch your eye. This is the Galata Mevlevi Lodge Museum which once was one of the homes to the renowned Whirling Dervishes. The Mevlevi Lodges were legally shut down in 1925 by the secular Republic of Turkey together with other religious lodges (tekke) and shrines (türbe) in the country. However, each year on December 17th, Mevlânâ Celâleddîn-i Rûmî (1207-1273) is commemorated on his night of death (named as Şeb-i Arus-his Wedding Day- by Rumi himself) in Konya (Turkey). The special ceremony symbolises his reunion with his beloved God. Whirling Dervishes performances also take place occasionally at the Galata Lodge and other venues in Istanbul throughout the year. You might want to check the dates to attend one of them during your stay in town. However, be warned that those outside the proper lodges are mostly performed as tourist attractions instead of the proper rituals.

Source: http://mevlanafoundation.com

The Galata Mevlevi Lodge (Galata Mevlevihanesi) is one of the rare original Ottoman style monuments in Beyoğlu. As you can observe, the Pera (Beyoğlu) district is architecturally dominated by Western trends of the time. However, the Lodge is much older than the Art Nouveau buildings in the vicinity. It was originally built in 1491, during the reign of Sultan Bayezid II (1447-1512), but had to be repaired or renovated numerous times in the following centuries. Damages were mostly due to earthquakes and big fires. The Galata Lodge is important because it is the first established Mevlevi Lodge in Istanbul and it played an important role in the dissemination of the Mevlevi Order (a.k.a. Mawlawiyya or Mevlevism) across the Balkans and Rumelia. The Mevlevi faith also found its way to Syria, Lebanon, Egypt and Palestine (especially Jerusalem) during the Ottoman era. In time, the number of lodges in the realm reached 114. The order became very popular among the Ottoman royals and the ruling officials after Sultan Bayezid I (1360-1403) married Devlet Hatun, a descendant of Rumi. Their son, the next Sultan, Mehmet Çelebi and the succeeding Sultans of the dynasty endowed the order with many privileges and sometimes with land. Members of the order were employed in important official positions across the Ottoman Empire.

Source: www.trthaber.com

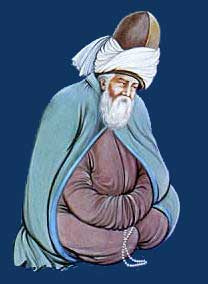

The Mevlevi Order is a Sufi tariqa (tarikat) that was established based on the teachings of Mevlânâ Celâleddîn-i Rûmî (known by the name of Rumi across the Western World). He was born in Balkh (in today’s Afghanistan) to Persian speaking parents. Later he became a great 13th century poet, Islamic scholar, theologian and Sufi mystic. His father, Bahaddin Veled (or Walad), was also a theologian and mystic and Rumi received his first education from him. When the Mongols invaded Central Asia (1215-1220), Rumi’s father set off towards western lands with his family and disciples. After long travels, including a pilgrimage to Mecca and several sojourns, they settled in Karaman (Turkey). In 1228 Bahaddin Veled, his family and entourage moved to Konya in Central Anatolia, most probably in response to the invitation of the Seljuk Sultan, Alâeddin Keykubad I (1192-1237).

Rumi took over his father’s lodge when he died. However, in time his contribution to Sufism and his fame surpassed that of his father. He mostly wrote in Persian (Farsi), but also occasionally used Turkish, Arabic and Greek in his verse. Mesnevi (a.k.a. Masnavi), which he wrote in Konya, is considered as one of the finest examples of poetry that was ever written in Farsi. Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi (a.k.a. Dîvân-ı Kebîr) is another major masterpiece by Rumi. His teachings were disseminated well beyond the borders of his country in the succeeding centuries. The humane approach of Rumi to all mankind and the absence of any requirement to be a Muslim to become a Mevlevi no doubt played a very important role in this spread across borders. The following lines that are attributed to Rumi say it all:

Come, come, whoever you are, come!

Heathen, fire worshipper or idolatrous, come!

Come even if you broke your penitence a hundred times,

Ours is the portal of hope, come as you are.

Rumi did not establish the Mevlevi Order himself. The principles were set long after his death in 1273. Institutionalisation began in 1292 under the leadership of his son Sultan Veled and his grandson Arif after him. The sheik of the Lodge in Konya was always chosen among the direct descendants of Rumi. The sheiks of the other Mevlevi Lodges that were established across the country over time had to be approved by the prime Lodge in Konya. Today, Rumi’s 22nd generation descendants have founded the International Mevlana Foundation in order to cherish Rumi’s legacy.

by Ignatius Mouradgea d’Ohsson (1740-1807)

Source: wikimedia.org

As previously mentioned, The Galata Mevlevi Lodge was established in 1491, more than 200 hundred years after the death of Rumi. Initially, it was known as the Kulekapısı (Towergate) Lodge. The founder of the lodge was the sheik of the Afyon Mevlevi Lodge, Divane Mehmet Dede. The land, which was probably donated, originally belonged to an Ottoman dignitary, İskender Pasha. According to some sources, during the Byzantine era there was a monastry (St. Theodore) on this spot and the cistern on the lodge’s premises is a remnant of the original structure. The turning point for the Galata Lodge was when Şeyh Galip Dede (1757-1799), a close friend of the ruling Sultan Selim III (1761-1807), became the sheik of the lodge. Şeyh Galip is one of the greatest poets of the 18th century Turkish literature and his mausoleum is inside the Galata Mevlevi Lodge complex. During his leadership, in 1791, the lodge underwent a major renovation with the support of Sultan Selim III who was also a Mevlevi believer. Following Sultans and their relatives continued to contribute to the maintenance of the premises. When lodges were shut down by law in 1925, the buildings were used as an elementary school for twenty years. In 1975 it was turned into the Divan Literature Museum. Unfortunately, many parts of the complex had already been demolished or destroyed by that time. Apart from the section that was sold to the Tünel Funicular Company (where now the Tünel Passage complex is), in 1942, part of its cemetary was turned into the Wedding Hall of the Beyoğlu Municipality. Unfortunately, many historical tombs and tombstones were destroyed during this construction. The Galata Mevlevi Lodge was reopened as a museum in 2011 following a major renovation and restoration.

Inside, there are also the cists of other Mevlevi dignitaries

St. Theodore in some sources

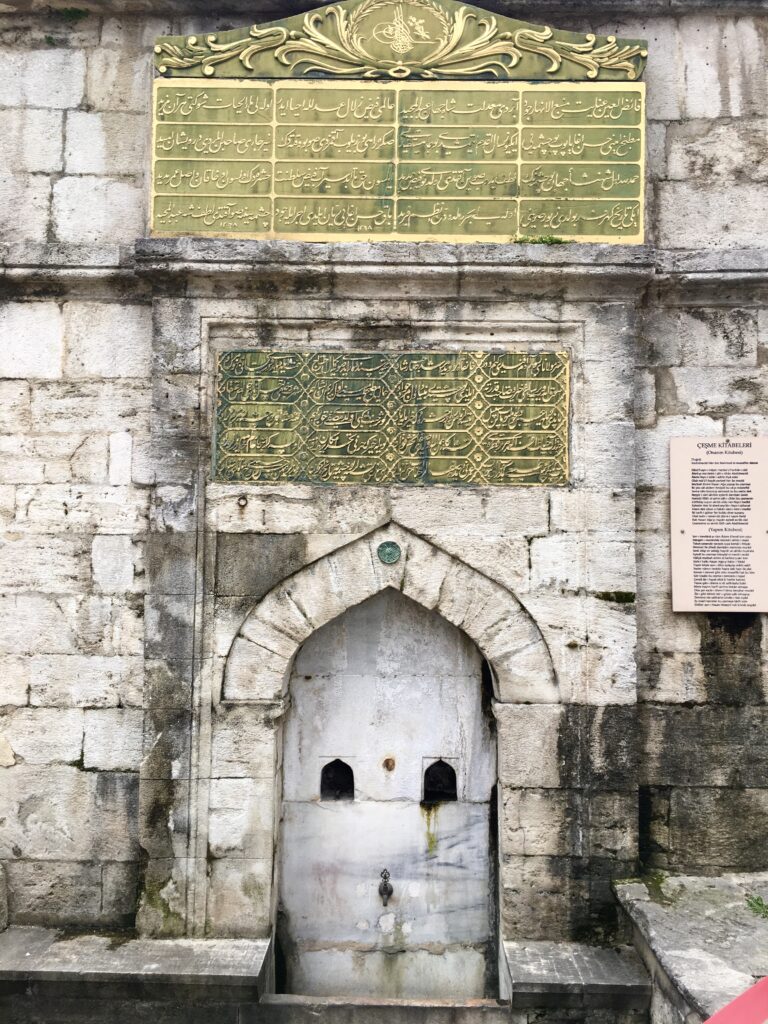

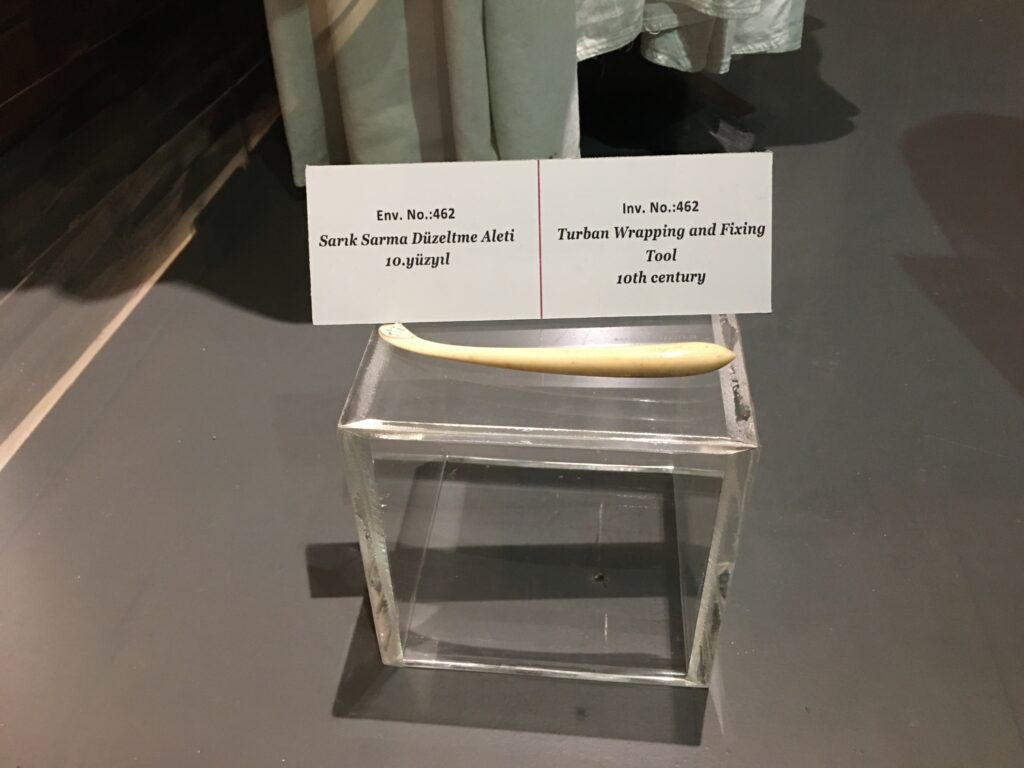

Today, the Galata Mevlevi Lodge stands on a land of 6800 square metres. It is organised in five sections. There are also two mausoleums on the grounds. Entry to the lodge is through a beautiful gateway. On the left-hand-side of the gate, there is the Mausoleum of Halet Efendi, an Ottoman statesmen. The building on the right is the Library of Halet Efendi and the muvakkithane (timing house) where time, especially prayer times, are correctly determined in addition to the astronomical and astrological studies that are pursued. The three-storey white structure facing the gateway is the actual building of the Galata Mevlevi Lodge and it is also where the museum collection is displayed. The building originally dates from 1796 but was later restored several times. It is called the Sema House (Semahane). The name comes from the special area inside the building where the sacred Sema ritual of the Mevlevis is performed. The famous whirling action is the major part of this ritual during which the dervishes transcend their material surrounding. On the ground floor, detailed information is given on Sufism, Sufi brotherhood and the Mevlevi way of life together with objects that were used and works of art that were created by them. All of these are displayed in the original Dervish Cells where they lived. The Sema area is on the second floor, an impressive round area with walnut floor boards. On the upper floor (originally the area of lodges overlooking the Sema area and the rooms behind) you can see works of art such as marbling and calligraphy. There is also a rich collection of musical instruments that were used by the dervishes. As an indispensible component of the Sema practice, music is very important for Mevlevis. In fact, there are numerous famous classical Turkish music composers (such as Itrî (1633-1711) and Dede Efendi (1778-1846)) and famous comtemporary music performers who belong to the Mevlevi Order.

Source: wikimedia.org

Source: wikipedia.org

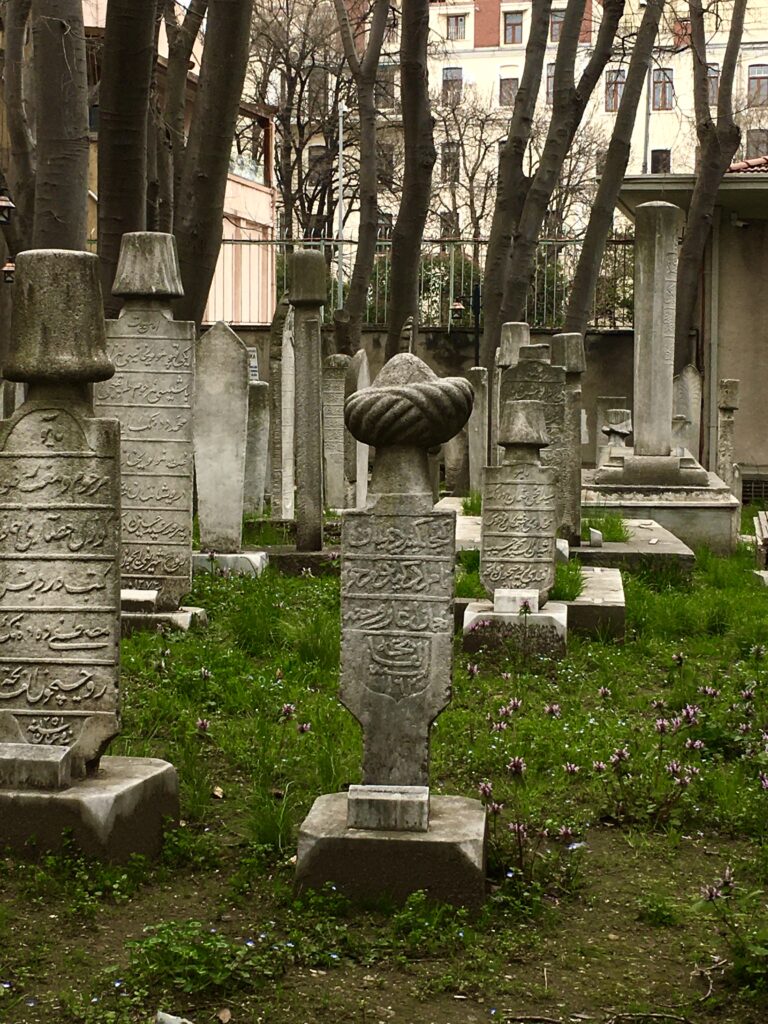

Before leaving, I recommend you to take a look at the cemetary as well. The cemetary is named as Hâmûşân, place of the silent ones, in the Mevlevi faith. Here you can see beautiful examples of Ottoman era tombstones. The deceased are Mevlevis from all walks of life, including a considerable number of females. Two of the tombs are especially interesting. They both belong to the group of renowned Ottomans who were originally Christians but converted to Islam at an adult age and offered their service to the Ottoman state. (The Ottoman devshirme (devşirme) system of recruiting young Christian boys to convert them to Islam and educate them for the higher ranks of the state is more widely known by foreigners. However, there were also a considerable number of Christian adults who voluntarily denounced their religion and rose to important military and bureucratic positions.) The first one of these is the Hungarian born and originally Christian İbrahim Müteferrika (1674-1745) who was an author, translator and printer. His greatest contribution was to establish the first printing house of the realm in 1727, where it was possible to print books written in the Arabic alphabet. (Previously books in Turkish could only be in manuscript form because the existing printing houses of the minorities could not publish books in Arabic letters. The Latin alphabet was acquired for the Turkish language in 1928 by the new Turkish Republic.) The second notable tomb is that of Humbaracı Ahmet Pasha (a.k.a. Kumbaracı Ahmet Pasha) who was originally a French aristocrat by the name of Count Claude Alexandre de Bonneval (1675-1747). He was a talented soldier and rose high in the army of King Louis XIV of France. Because of his bad temper, he changed sides several times among different European kingdoms, even fighting against his own country from time to time. He later converted to Islam and offered his service to Sultan Mahmut II, taking the name Humbaracı Ahmet Pasha. Humbara is a kind bomb used in artilllery. Humbaracı Ahmet Pasha contibuted greatly to the modernisation of the Ottoman army by establihing a special school in 1729 and forming the humbaracı corps.

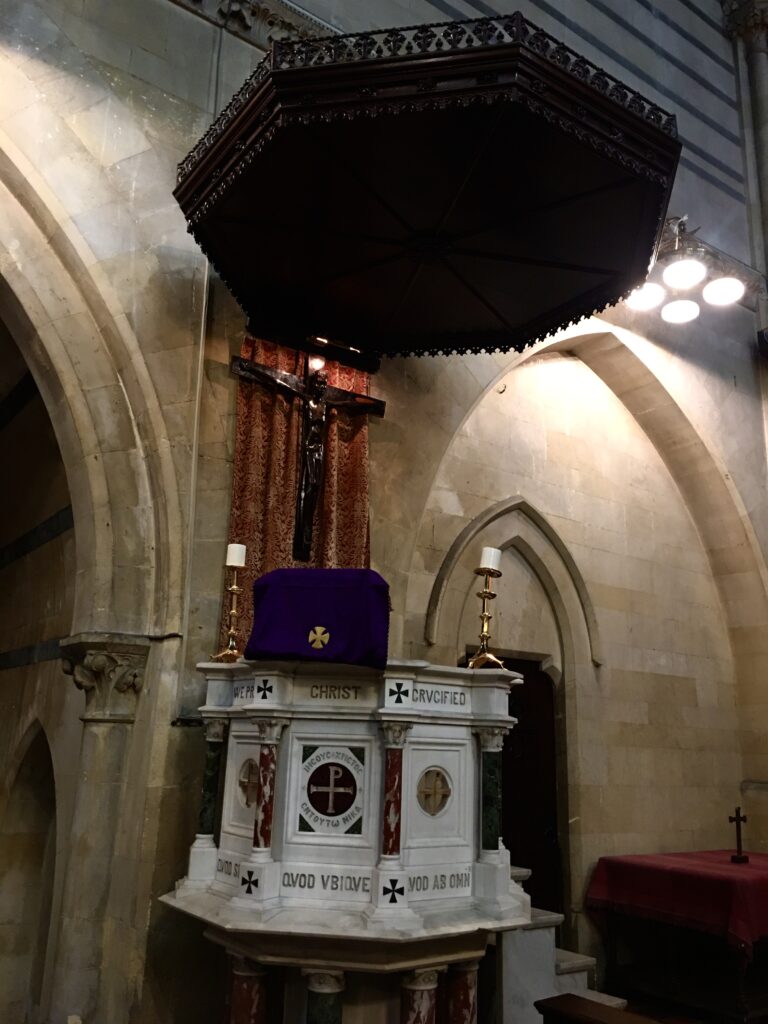

Not far from the Galata Mevlevi Lodge Museum, there is the Crimean Memorial Church in Galata (Serdar-ı Ekrem Cad. No: 52). There are several routes you can follow to the Crimean Memorial Church. I prefer going back up to the İstiklal and then down again via the Şahkulu Bostan Street. On the way, you will see beautifully renovated old buildings some of which are now home to boutiques and small artisanal shops. The church, which is also visible from the Galata Tower, was built in 1868 by the British government, in memory of those who died during the Crimean War (1853-1856). It is an Anglican church, built in Neo-gothic style by the British architect G.E. Street, who is also the architect of the Royal Courts of Justice in London. The British Empire was, together with the French, an ally of the Ottoman Empire against the Russians during the Crimean War. British losses were immense even though the outcome was victorious for the allies. The church was built in memory of those who lost their lives. The land was donated by Sultan Abdülmecit (1823-1830). Ground breaking ceremony was held in 1858. However, it took ten years to build the church and was inaugurated at the time of the following Sultan, brother of Abdülmecit, Sultan Abdülaziz (1830-1876). The black stone blocks of the structure were brought from Büyükada (a.k.a. Prinkipo– The biggest island among Princes’ Islands), the yellow ones countering the windows and corners were from Malta. Currently, the church is mostly used by the African community in Istanbul.

Source: Onedio.com

Source: Onedio.com

If you prefer to end your excursion at the Galata Tower, you can continue to walk along the winding Serdar-ı Ekrem Avenue. Do not forget to watch out for the building at number 30. This beautiful building, that is bound to attract your attention, is known as the Doğan block of apartments. It was built in 1894 by two Italian architects, for the Belgian banker family Helbig. The complex is a U shaped structure with a courtyard in the middle. The open side of the courtyard yields a mesmerising view. Unfortunately, non-residents are not allowed on the premises anymore because of the increasing number of people over time who wanted to see the structure and the view. I personally had the opportunity to enter the courtyard a couple of decades ago when it was open to the public. It is stated that, this is the first block of apartments that had a lift in Istanbul. The building changed hands a couple of times and its name also changed with each transaction. The building acquired the name Doğan from its Turkish banker owner Kazım Taşkent‘s son. When his son died at a very young age, Mr. Taşkent sold the building. It is now home to numerous Turkish artist(e)s, academicans and intellectuals.

To share this post

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

About the author

2 comments

Comments are closed.

Such an excellent, detailed and informative post from a part of Istanbul I thought I knew pretty well. Thank you

Thank you for your time and comment. It will be a great motivation for my future posts.