Looking at the Old City from the opposite coast of the Golden Horn, from left to right, you will see the Topkapı Palace (1478) and the immaculate Hagia Sofia (537) at first sight. The two of them, so close to each other, mark two different eras of this ancient city. Two empires which, according to some historians, are in fact a continuation in many respects, regardless of the differences in language and religion. What could be better proof of this point of view than the minarets of Hagia Sophia that were later built by the Ottomans, so beautifully blending with the original structure?

While Topkapı, with its Tower of Justice and numerous pavilions, is reminiscent of the later Ottoman times, Hagia Sofia, with its huge dome, is the incontestable symbol of the East Roman or Byzantine past of Istanbul. Both of them deserve to be well preserved and protected as a heritage that belongs not just to Istanbul, but to all humanity as well.

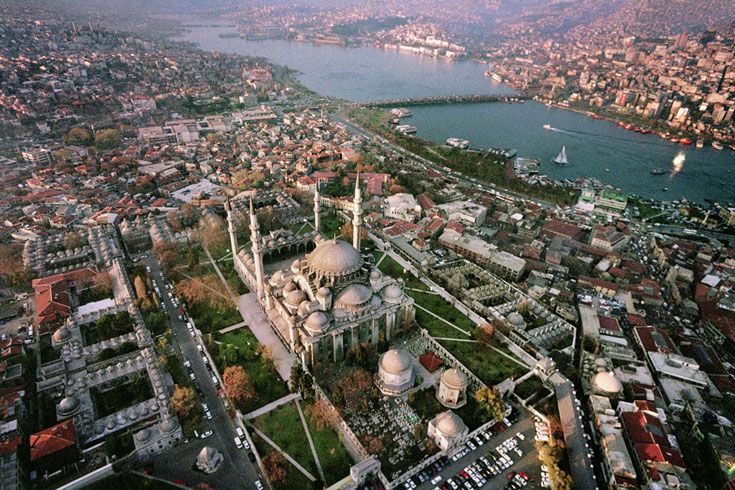

As you try to take in this beautiful scenery, depending on your location, you can also see the Sultan Ahmet Mosque (1617) known by foreigners as the Blue Mosque because of its beautiful blue tiles. Yet, further to the right there is one breath-taking structure, the stupendous Süleymaniye Mosque (1557), that you can not miss. Built one thousand years after Hagia Sophia, this elegant mosque stands as if to balance the landscape while majestically rising above the Golden Horn.

The Süleymaniye Mosque is the second largest imperial mosque complex in Istanbul. Unfortunately, the majority of tourists coming to Istanbul miss this magnificent historical and architectural structure during their visit. Most tourist itineraries suffice with the Sultan Ahmet Mosque instead of this more important and (in my opinion) more impressive mosque. This may also be due to the location of the former mosque. Apart from its beautiful tiles, the Blue Mosque is also very convenient in terms of its proximity to the Topkapı Palace and Hagia Sophia. However, I would definitely recommend a visit to the Süleymaniye Mosque if time is not a constraint for you.

Photograph by Ara Güler

Turks call him Kanuni Sultan Süleyman because of the laws (kanun in Turkish) he made. Sultan Süleiman the Law Maker. Foreigners call him Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. Maybe because, while fearing him because of his conquests east and west, deep down they admired him. He was the tenth Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. He ascended the throne at the age of twenty-five in 1520 and ruled the empire until his death in 1566. His was the longest and most glorious reign in the history of the Empire. As a result of his numerous military campaigns he captured Belgrade, the Greek island of Rhodes, Baghdad and Tabriz from the Safavid dynasty, parts of Georgia, Moldavia and Romania. He established a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire in Hungary after four very successful campaigns to the country. The two sieges of Vienna (in 1529 and 1532) and the siege of Corfu (then held by the Venetian Republic) in 1537, together with the second invasion of Apulia (South Italy) by the Ottomans in history, also made their marks on European history even though they were not successful. He died during his last campaign to Hungary when the city of Szigetvar was besieged. The city fell the day after the Sultan died in his tent. His death had been kept as a secret from the Janissaries (soldiers of the Ottoman army, called Yeniçeri in Turkish).

With so many glories, Suleiman deserved to have a majestic mosque complex built in his name, in the imperial city. All three of his ancestors who reigned after the conquest of Istanbul, each had a mosque complex in their names. So, Suleiman would also have a mosque that matched his fame. As for the architect, who else would be more appropriate for the task than the chief architect of the empire, Mimar Sinan, at the time? The Great Sinan is an extraordinary Ottoman architect whose creations continue to fascinate us to this day.

Sinan was the child of Christian parents from a small village in Cappadocia, in Central Anatolia. His birth date is believed to be around 1490. He was converted to Islam and taken into the Sultan’s service, as was the custom at the time. He then became a military engineer and participated in four of Suleiman’s military campaigns, before being appointed as the Chief of Imperial Architects in 1538. He not only served Suleiman the Magnificent, but also his son and grandson, Sultan Selim II and Sultan Murad III. By the time he died in 1588, when he was 98 years old, he had adorned not only Istanbul, but almost every corner of the Empire with the most beautiful examples of Ottoman architecture as well. Today, some of these are outside the borders of modern Turkey. Among his work are 107 mosques (out of which 42 are said to be in Istanbul), 52 mescits (buildings much smaller than mosques for praying), 74 madrasas (schools for Islamic theology), 56 Turkish Baths, 3 hospitals, 45 türbes (mausoleum type tombs), 22 public kitchens, 31 caravanserais, 11 schools, 43 palaces, 9 bridges and 7 aqueducts.

After becoming Chief Imperial Architect, Sinan’s first work in Istanbul was the Haseki Hürrem Sultan Mosque (1539) which was commissioned by Suleiman the Magnificent for his beloved wife. (The complex around the mosque was built much later (1551) under the instructions of Hürrem Sultan.) The second mosque built in Istanbul by Sinan was the Şehzade Camii, also commissioned by the Sultan for his beloved Prince (Şehzade) Mehmet, who died at the age of 22 in 1541. The mosque was built between 1543 and 1548. So, it was evident that, when Suleiman decided to have a grand mosque built in his name on the Third Hill of the Old City, the architect was going to be no one else but Sinan again. The construction began in 1550 and took seven years to complete. Even though Sinan does not name the Süleymaniye Mosque as his greatest work of art, it is nevertheless a breath-taking and beautiful structure that almost mesmerises you. The perfect combination of the best examples of Islamic art with a meticulous building technology that also takes efficiency and recycling into account. A true feast for the eyes and the mind…

The location of the Süleymaniye Mosque, which was chosen by the Sultan himself, doesn’t seem to be a mere coincidence. Looking from the other side of the Golden Horn, from the Genoese quarter, it clearly gives the message about which empire is ruling the city. The land was mostly part of the Old Palace which was built after Istanbul was conquered. However, the expropriation of the remaining land and the preparations for construction took two years.

In his book, Süleymaniye, the renowned Greek historian, Stefanos Yerasimos (1942, Istanbul- 2005, Paris) gives very interesting details about the construction process of the mosque. According to him, the detailed ledgers that are currently kept in the archives of the Topkapı Palace clearly show the names of the workers and the foremen, the days of the week that each of them worked on, their pay days, their origins by religion (Muslim or non-Muslim) and by social status (free workers or slaves). It is also stated that, according to the 165 ledgers in the archives, the construction took 2,678,189 work days. The estimated average number of workers per day is 1674 people.

According to Yerasimos, the main driving force for building Süleymaniye as it is, was to surpass Hagia Sophia. Inspired by the unique Byzantine architectural wonder and tempted by the political message that would be given if succeeded, Yerasimos says the greatest of the Ottoman architects, Mimar Sinan, sought to achieve this aim as much as the landscape and technology permitted at the time. The slightly ellipse dome of Hagia Sophia was evidently the significant area of competition for the architect. The diameter of the dome of Hagia Sophia is between 30.9 and 31.80 metres. The height, measured from the keystone of the dome to the ground, is 55.60 metres. Süleymaniye, as grand and majestic as it is, has a dome diameter of 27.5 metres and a height of 47 metres. Therefore, Sinan could not surpass Hagia Sophia with Süleymaniye, but he succeeded in doing so later (at least in terms of the diameter of the dome, if not in height), when in 1575 he completed the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne for Sultan Suleiman’s son, Sultan Selim II.

The Süleymaniye Mosque is inside the usual porticoed courtyard encountered in grand Ottoman Mosques. The high granite and marble columns immediately give you a sense of grandeur as you set foot in the courtyard. The main portal to the courtyard, on the west side, is flanked by a two-storeyed structure with chambers that are said to have belonged to the mosque’s astronomers. The four great minarets of the mosque are situated in each corner of the courtyard. These four minarets are said to represent that Suleiman is the fourth Ottoman Sultan reigning in Istanbul, while the total of ten balconies (called şerefe) on the four minarets denote that he is the tenth Sultan of the Imperial line.

When you enter the mosque itself, the feeling of grandeur once again takes hold of you. However, apart from the vastness, this grandeur also comes from its simplicity. The refined stained-glass windows, the earliest examples of the beautiful İznik tiles, the marble of the mihrab and the minber (pulpit), the woodwork inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl and the inscriptions throughout the building, all contribute to the beauty of the interior. The mosque was heated from below. A natural ventilation system was created with the use of very small holes in the walls. This ventilation system was also designed as a means of absorbing the soot created by the smoke from hundreds of lanterns. By use of the air current inside the mosque, the soot was collected in a special chamber. The collected soot later provided calligraphers with excellent material for writing.

The Süleymaniye Mosque went through a great fire in 1660. It lost some of its originality when it was restored in the mid-nineteenth century by the Italian-Swiss Fossati brothers upon the order of the Sultan of the time. It gained a more Baroque style after that. The courtyard was used for keeping ammunition and weapons during World War I. The ignited ammunition caused another big fire and the mosque was not fully restored until 1956.

When you leave the mosque by its north door, you step on to a terrace that overlooks the Golden Horn. Here, over the chimneys and the little domes of the madrasa cells and the public bath below, you will be looking at one of the most beautiful sceneries in Istanbul.

Turning your back to the Golden Horn and facing the mosque again, to the left you will see a walled garden where the mausoleums of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and Hürrem Sultan are. Suleiman was devastated when the love of his life, Hürrem Sultan, died in 1558. The largest of the two, naturally belongs to Sultan Suleiman. It is octagonal and surrounded by a porticoed porch. Inside, the tiles and the painting in the dome are beautiful. However, the crowd of visitors almost always prevents you from fully taking in the details. Early hours of the day would certainly be better for a visit. The biggest cenotaph in the mausoleum belongs to Sultan Suleiman. Next to him are those of his daughter, Mihrimah Sultan, and two later Sultans (Suleiman II and Ahmet II) in the hereditary line. The practice of burying several Sultans in the same mausoleum was quite common in Ottoman times.

The Süleymaniye Mosque complex covers a large area including the streets around and below the mosque’s territory. Originally, it included 6 madrasas (including one as a medical school), a hospital (bimarhane), a public kitchen (darüzziyafe), a guesthouse (tabhane) and a Turkish bath. Unfortunately, some of these buildings, such as the hospital, do not exist anymore. Others are used for other purposes.

Before you leave, make sure to pay a visit to the türbe (tomb) of the great architect of Süleymaniye, Mimar Sinan. It is in a little garden, beautifully situated in a street corner, below the north west corner of the complex. The architect lived here for many years and he designed and built it himself. Beside his grave with a big turban shaped tombstone, there are also the tombs of his wife and children. The long inscription on the wall of the türbe’s garden is by the architect’s poet friend Mustafa Sa’i, commemorating Sinan’s lifelong accomplishments.

[…] idea of visiting the Süleymaniye Mosque and its environs always comes to my mind together with a much loved threesome of the Turkish […]