The Sultan Ahmet Square is considered as the historical centre of Istanbul. This is a fact that anyone, local or foreigner, would concur without much ado. Even though historical monuments, whether visible or still waiting to be excavated, are abundant all over the city, this is the cradle of the ancient city of Istanbul. Situated on the First Hill, it is the area that outlived three empires. Therefore, it is also the main centre of attraction for visitors with all the basic places on their “to see” lists for Istanbul. The immaculate Hagia Sophia, the magnificent Topkapı Palace, the enchanting Basilica Cistern and the Sultan Ahmet Mosque with its beautiful blue tiles are all in the vicinity. Visiting these places would pretty much give you an idea about the history of the city, especially if you have a time constraint. However, the area also has some hidden away museums that are just as much valuable and interesting. They await visitors who are willing to take that extra step which will open new gateways for a more in-depth insight of the culture and history of these lands. The Carpet Museum is one of those secluded and extremely interesting museums that is recommended if you have the extra time.

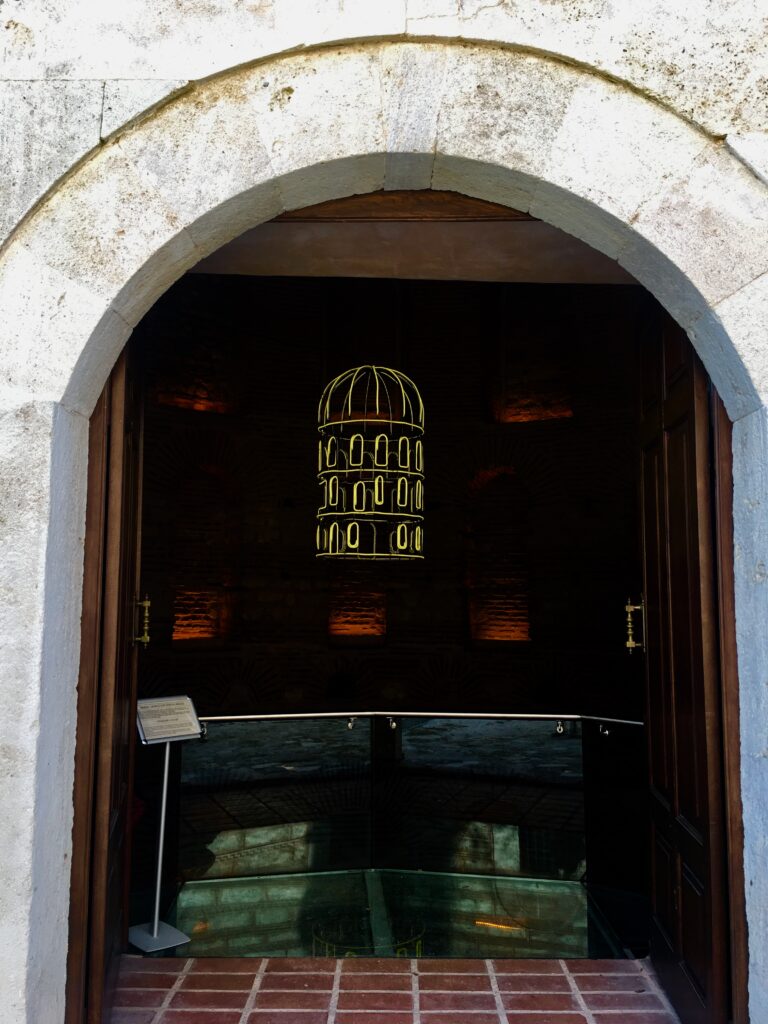

The Carpet Museum is on the premises of the Hagia Sophia Museum. However, access is through a separate entry at the back. Walking from Hagia Sophia to the Topkapı Palace (keeping the Basilica on your left), you will see a grand Ottoman style portal right at the corner of the street between Hagia Sophia and the palace walls. This is the corner of the Soğukçeşme Street. (For more information about this historical street, you can read the post Fine Dining in the Old City). Entering through this portal you will not only be able to visit the Carpet Museum, but will also be able to see The Treasure Chamber (Skeuophylakion) of Hagia Sophia as well. This circular building with a dome was where the sacred and precious objects utilised in religious rituals in Byzantine times were kept. The contents were most probably ransacked during the invasion of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. The opinions of experts and historians about the time of construction of the building range from 4th to 6th century A.D. Until the last quarter of the 19th century, the Ottomans used the building as a larder for the public kitchen (imaret) that was built here for the poor. After that, it was used as an archive building for some time.

The Carpet Museum is in the above-mentioned public kitchen buildings. Inside, you can still see the stone stoves that were used at the time. Public kitchens on the grounds of big mosques were very common in Ottoman times. Since Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque (without changing its name) in 1453 by the order of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, it is not surprising that a kitchen for the poor was built here too.

The carpets that are on display in the museum are part of the collection of the General Directorate of Foundations of Turkey. The collection itself is stated to be one of the richest carpet collections in the world and it mainly consists of carpets that were donated to mosques, shrines and Islamic complexes over the centuries. The collection comprises carpets woven between the 14th and 20th centuries, including rare ones from Iran and the Caucasus region. 394 out of the 806 carpets in the collection are regarded as historical ones. The 40 carpets that are on display are among the rarest pieces of the collection.

The carpets and rugs in the museum are arranged chronologically and according to their design characteristics. In the first gallery, there are carpets from the Anatolian Seljuk state period. In the second gallery, Ottoman era Central and Eastern Anatolia carpets are on display while ancient carpets from Uşak area and prayer rugs are in the third gallery.

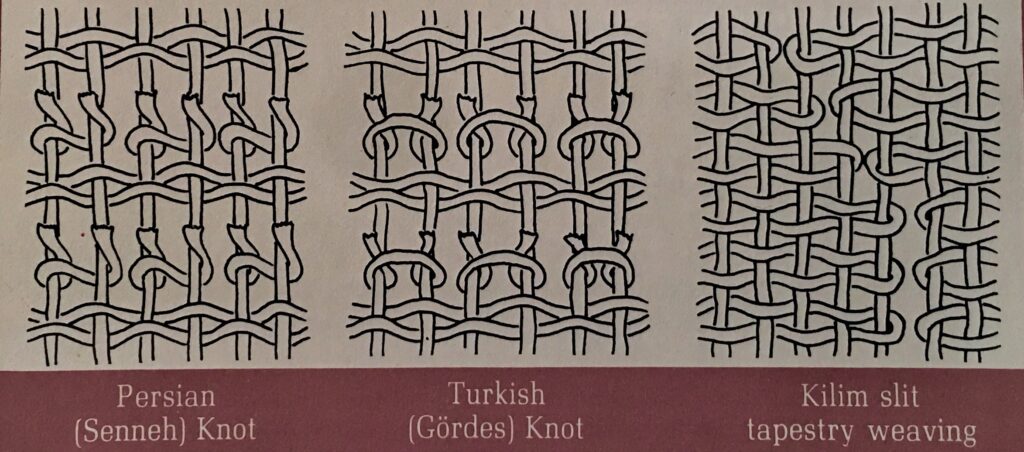

It is a well known fact that, Turkish carpets have a worldwide fame. They are renowned for their patterns, colours, quality and beauty. They differ from Persian rugs in the way the knots are made while weaving. Although both flat-weaving and knotted-pile techniques have been used by Turks for thousands of years, an authentic and valuable Turkish carpet is usually presumed to have been woven with the latter.

The craft of carpet weaving is an historical heritage for Turks from their nomadic past. Hand-made carpets and rugs are still used with pride and pleasure in Turkish homes. Although increasing prices in the past few decades have turned them into luxury goods, they are still widely craved for, even by low income classes.

Carpets and rugs, in fact all kinds of woven goods, were important in the nomadic life of Turks in Central Asia. It was an important part of their culture. Being nomads, their life was dependant on husbandry and animal products. Wool was at their disposal. On the other hand, they had the need for tents, bolsters, cushions, bags and carpets. They discovered how to shear the wool of their sheep, to clean and turn it into yarns using a spindle. They extracted dyes from plant roots, insects and flowers in their environment. Using wooden frames, they wove the articles they were in need of in their daily lives. Meanwhile, they did not cease to look for and to create beauty. This natural instinct of mankind made them create patterns and colour combinations that are still inherent in Turkish carpets.

All woven materials, including carpets and rugs were made exclusively by women and they still are. Flat-weaving and knotted-pile techniques were already traditional among Turks in Central Asia which means that this Turkish craft is more than two thousand years old. However, even if Turks brought the techniques, the know-how and their typical patterns to Anatolia, they were no doubt also influenced by the existing culture and heritage they encountered here. As Mr. Mergen, who is a business professional and expert in this field, beautifully states, “Anatolian carpets are the common language and shared cultural heritage of all people who ever called Anatolia their homeland”… (For more information, you can read the post Blooming Flowers in Caria).

Officially, the 26th of August 1071 is considered as the date when Turks set foot in Anatolia. This date refers to the battle of Malazgirt (Manzikert) in Eastern Anatolia between the Turkish Seljuk Empire and the Byzantine Empire. The victory of the Turkish army led by the Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan was sealed by the capture of the Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV. Diogenes. However, today it is known that Turks began to settle in Anatolia under the Byzantine reign long before that date.

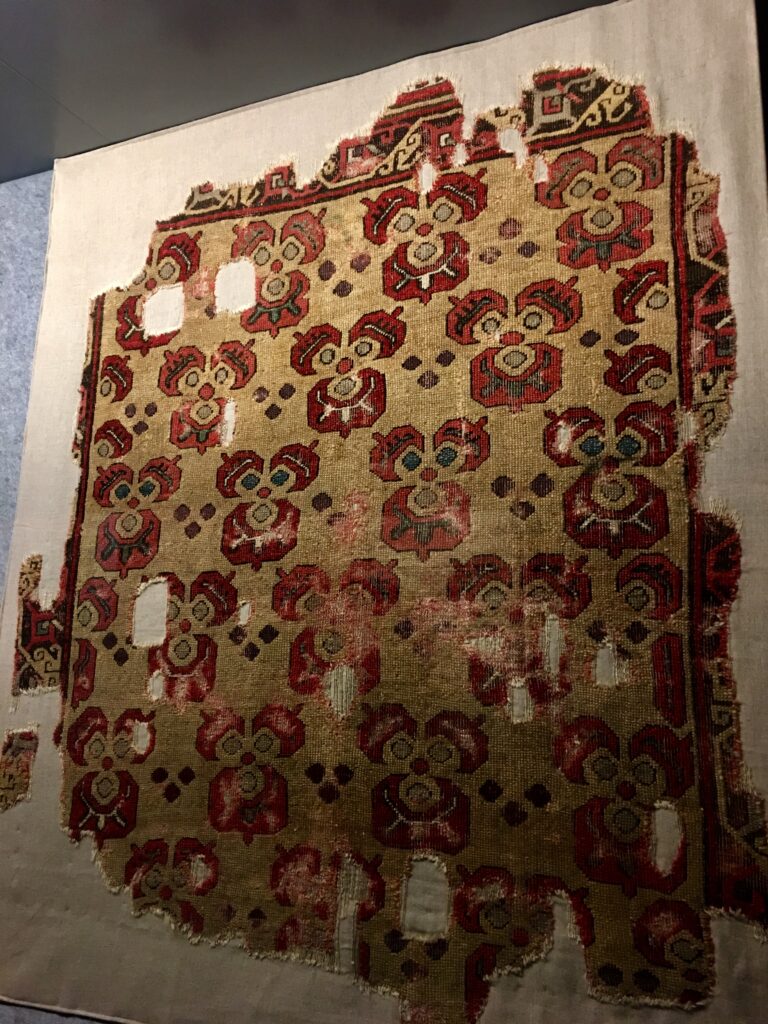

The oldest carpets displayed in the museum are from the Anatolian Seljuk Empire period (1075-1308). Turkish carpet weaving continued without interruption in these new lands. Marco Polo described the Turkish carpets of the Seljuk era as the “the finest in the world”. The legacy was carried on by the independent small Turkish states (Beylikler) that sprung up in Anatolia after the fall of the Seljuks. The carpets of this era (14th-15th century) are called the “Beylikler Era Carpets”. They are richly adorned with animal figures. Apart from flowers and animals, decorative elements of the Seljuk architecture were also a source of inspiration for these carpets. Seljuk ceramic and tile patterns surrounded by cufic inscriptions gave these carpets a monumental appearance.

Interestingly, European paintings have been a primary source to trace the history of Turkish carpets. Numerous paintings and frescoes, such as those of Giotto in the Arena Chapel of Padua, depict Turkish carpets that were most probably imported by Venetian merchants as of the beginning of the 14th century. As Turkish carpets became luxury items for European palaces and the mansions of the upper classes, they became increasingly illustrated by the artists of the era. Eventually, these carpets took the names of the artists who depicted them in their paintings. Thus, certain types of Turkish carpets were named after the Renaissance painters, such as Hans Holbein and Lorenzo Lotto, who painted them. Examples of these carpets can be seen today at the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts in Istanbul.

The National Gallery, London

The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

The early age Ottoman era Anatolian carpets that are named as “Holbein or Lotto Carpets” are characterised with depictions of animals, plants and geometric motifs that are set in squares and rectangles. They are mainly divided into four types according to the variations in their patterns. These 14th and 15th century carpets are considered as a transition to the Classical Period in Ottoman carpet weaving.

Similar to the development that took place in other branches of art, the rise of the Ottoman Empire brought about significant changes in carpet weaving. Thus, 16th and 17th century carpets differed from previous ones in terms of form and pattern. The carpets of this period consist of Uşak (a city and its surroundings in Western Anatolia) carpets and Palace Carpets. Uşak carpets are the largest and most well-known group of Turkish carpets. They are considered as the type of carpets with the highest quality. Uşak carpets are grouped under four major patterns. Namely, the Medallion, Star, Chinese Cloud and Bird carpets.

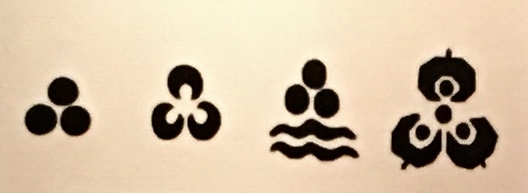

The Chinese Cloud (Çintemani) is a pattern that can be seen in almost all branches of Ottoman art. The origin of this pattern is Central Asia and Turks have brought it to their new lands. The symbol is said to be first used in Buddhist art. Having acquired it, Ottomans used it on carpets, tiles, Sultan and Şehzade (crown prince) garments and caftans as a sign of power, nobility, might and good fortune. It consists of three dots and two wavy lines. The dots signify three leopard dots and the wavy lines stand for tiger stripes.

Ottoman Palace Carpets have an important place in the history of Turkish carpet weaving. They were ordered by the palace and produced under a strict surveillance. They differed from regular carpets in terms of technique and patterns. The conquests of Cairo and Tebriz are considered as turning points for Palace Carpets. They were clearly influenced by the weaving techniques and patterns that were used in those countries. The Palace carpets were woven with silky wool. Some of them were produced very thin, to be used as table cloths.

Central and Eastern Anatolia carpets stand out with their own patterns. They mostly have a serrated-edged or star-shaped medallion at the centre.The most beautiful and best quality carpets in this group belonged to the cities of Konya, Karapınar, Sivas and Divriği in Central and Eastern Anatolia regions.

The way of praying in Islam created a high demand for carpets to be used in mosques. Among these, the Uşak “Saf Prayer Rugs” have a special place. These are prayer rugs that are one piece but with multiple mihrabs (niches) side by side. They enabled the congregation to get in line (called saf in Turkish) and pray on them together at the same time. These types of prayer rugs in the collection of the museum date from 15th to 19th centuries.

17th century (at the top), originally from the Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul.

19th century (at the bottom), originally from the Sultan Ahmet Mosque, Istanbul

Although Turkish carpet weaving may seem to be confined to strict rules of techniques and patterns, there is still room for the inspiration and creativity of the women who make them. By means of a language of motifs established over centuries, they find ways of expressing their sorrows, longings and joy. They might be mourning over a lost child or be yearning for a loved one who left long ago… All woven for expert eyes to see and understand. Spending hours in front of the loom, they have all the time they need for an inward journey. Some hide an initial or even a lock of hair, carefully woven together with the wool, experts say…